“A New Kind of Art Object”: Tracing a History of Performance at MCA Chicago in the Museum’s First Decade

by Jenny Harris, Curatorial Fellow

The MCA DNA Research Initiative is a multi-year curatorial program, supported by the CHANEL Culture Fund, that invites early-career curators and writers to the museum for interdisciplinary research projects related to the institution’s collection. Focused on the intersection of visual art and performance, this initiative surfaces overlooked art historical narratives within the organization’s history while foregrounding the cross-disciplinary ethos that has been integral to the museum since its founding in 1967. The following essay was written by program participant, Jenny Harris, upon the conclusion of her research project.

Since the early 2000s, performance has become a fixture of museum programming, whether the subject of art historical exhibitions or as parallel events designed to broaden the scope of the artistic experiences on offer. The roots of this trend can be traced to the 1960s and 1970s, when museums pioneered new ways of accommodating an evolving range of performance-based practices. In examining this trend, art historians have tended to focus on the activities of a select few large institutions, primarily Tate Modern in London, with its inauguration of The Tanks as a dedicated performance space in 2010, and The Museum of Modern Art in New York, with its 2009 rebranding of the Department of Media as the Department of Media and Performance Art and the opening of its own dedicated performance space in 2019.[1]

Smaller institutions, however, have often served as the critical testing grounds for new performance-based work, taking chances on emerging and little-known artists and working nimbly to stretch the museum’s capacity to accommodate live arts programs. In the United States, this is especially true in the Midwest where institutions like the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the Wexner Art Center in Ohio have pioneered performance in the museum for decades.

Like such institutions, the history of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago is tethered to the development of the history of performance and to the emergence of the phenomenon of performance in the museum. Though it appeared in fits and starts, performance was integral to the MCA’s founding ethos and a central component of its first decade of programs. Increasingly synonymous with the most cutting-edge artistic practices, presenting performance was a key means of demonstrating the museum’s founding mission to promote the work of the most relevant living artists. Over the course of its first decade, the performing arts appeared in several guises: as a thematic concern in visual art exhibitions (often a compositional strategy or a mode of interaction in the production of objects), in the form of public programs designed to showcase emerging performance practices, and as a public relations strategy designed to demonstrate a range of artistic disciplines and attract new museum audiences. Such efforts to foster performance were complicated by the museum’s shift away from its founding model as a contemporary Kunsthalle. As the MCA embraced a new status as a collecting institution, that change produced tensions that continue to define its approach to performance in the museum, and that raise questions about the relationship between ephemeral performance-based practices and the care of valuable objects.

Jan van der Marck and the Contemporary Kunsthalle

The MCA opened its doors in the fall of 1967 at 237 Ontario street in a converted bakery most recently vacated by Playboy Enterprises. This location, the heart of Chicago’s active gallery district at the time, suited the fledgling institution’s mission to present the most cutting-edge art of the day and to thereby spur the city’s community of artists. For the museum’s founders—prominent collectors like Joseph Shapiro and Lewis Manilow and its first director, Jan van der Marck—contemporary art called for a new kind of institution. Unlike the Art Institute of Chicago, an encyclopedic collection where “the values of the past are enshrined,” the MCA sought instead to model itself on the German Kunsthalle, dedicated to temporary exhibitions and events, rather than the safekeeping of precious objects.[2] The new museum would prioritize the work of the most cutting-edge living artists.

Van der Marck, a Dutch-born art historian who arrived in Chicago after working as a curator at the Walker Art Center, was the primary architect of this vision. In the late 1950s, on a grant funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the junior scholar spent two years studying the success of then-establishment institutions like The Museum of Modern Art. Van der Marck’s repeated assertions that the MCA be a “place of experiment, a proving and testing ground, a laboratory,” reflect his conscious appropriation of the earlier rhetoric of MoMA’s own founding director, Alfred Barr.[3] The success of the Chicago museum, he believed, depended on its ability to mimic what he saw as the recipe for MoMA’s triumph in the 1930s: foregrounding idea-driven exhibitions over the cultivation of the collection, and a radical openness to the incorporation of a wide variety of artistic media. As we will see, performance emerged organically as an extension of these wider, intermedial aims.

Whereas Barr’s approach to the presentation of diverse media rested on the formation of distinct collecting departments, devoted not just to the traditional media of painting and sculpture, but to “drawings, prints, and photography, typography, the arts of design in commerce and industry, architecture . . . stage designing, furniture and the decorative arts,” Van der Marck wove an embrace of multiple media into the thematic of temporary exhibitions.[4] This strategy shaped the MCA’s opening season, which featured an exhibition of photographic documentation of Happenings by two of the genre’s pioneers, Allan Kaprow and Wolf Vostell, with the emphatically mixed-media exhibition Pictures to be Read / Poetry to be Seen.[5] These opening displays—each with a clear commitment to performance-based practices—offered a preview of Van der Marck’s subsequent three-year tenure at the museum in which he consistently paired exhibitions related to performance with the programming of live events. By doing so, he placed performance at the heart of the museum’s evolving vision of contemporary art.

Pictures to Be Read / Poetry to Be Seen

In our contemporary world the traditional boundaries separating painting, sculpture, theater, dance, poetry, literature and music no longer exist.

So declared the MCA’s press release for its opening exhibition, Pictures to Be Read / Poetry to Be Seen. “We are witnessing a syncretism of the arts, an overlapping of media. . . . Today, painters are cinematographers, sculptors are choreographers, poets are playwrights, physicists are composers and many of them combine forces to create environments, happenings and theater events.”[6] To illustrate the point, Pictures convened 68 works by 12 artists drawn from five countries. They were united by a shared consideration of the relationship between words and images—a combination that set the “temporal element” of words against the “spatial domain of the image.”[7]

Van der Marck’s accompanying catalogue essay traced the origins of this contemporary body of work to the innovations of Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, charting the recent proliferation of practices deploying innovations in chance procedures, conceptual play, and interdisciplinarity. In a basic sense, the Pictures works enacted a kind of performance through implied or actual forms of viewer interaction. Works by Swedish artist Öyvind Fahlström, for example, involved objects that could be manipulated at the viewer’s discretion such that “the finished picture,” Van der Marck explained, “stands somewhere in the intersection of painting, games and puppet theater.”[8] Ray Johnson’s collages, on the other hand, were the result of a “postal performance,” in which he sent the artworks’ raw materials through the mail.[9]

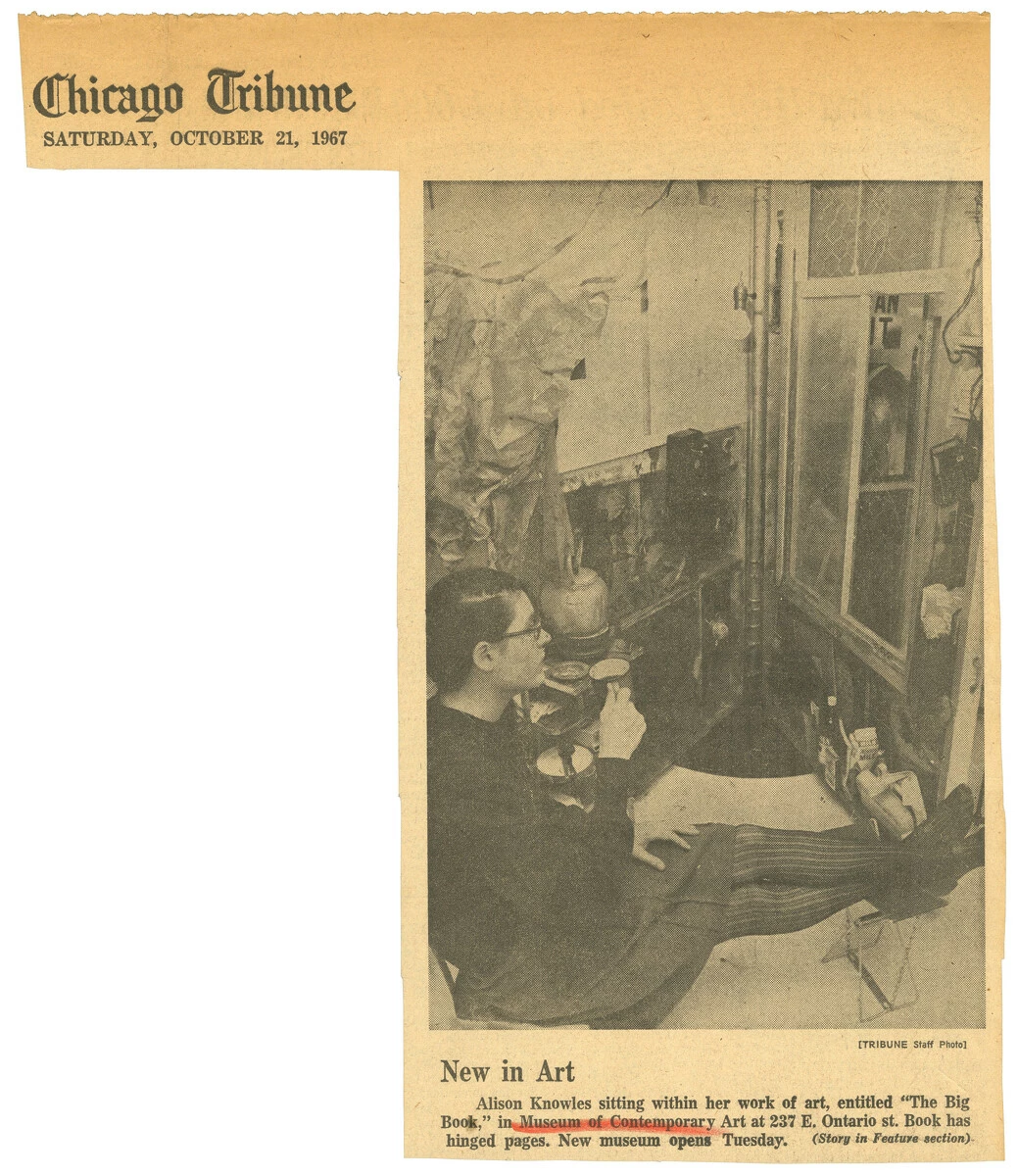

The exhibition’s driving ethos of performative “intermedia” was perhaps best expressed by the Fluxus artist and Happenings pioneer Alison Knowles, who contributed The Big Book (1967, fig. 1), an eight-foot assemblage of 8 x 4 feet pages comprised of overlapping, silkscreened images and various domestic objects including a stove, a telephone, and an electric fan.[10] “No medium has been left out of this ‘Book;’” wrote the critic Harold Rosenberg, a professor in the University of Chicago’s department of Social Thought between 1966 and 1978. “It is audio-visual, kinetic, electrified, mobile. It makes use of painting, sculpture, film, silk screen, mirrors, colored lights, double images, carpentry, welding.”[11] Visitors were invited to “enter” and freely manipulate the human-scale artwork, a fact that made it exemplary of Van der Marck’s thesis concerning the contemporary “dissolution of the barriers that separate art from life.” The Big Book, he argued, “not only sets the stage for, but through various additive devices such as light, taped sound and a live telephone and hot plate partakes in the action.”[12]

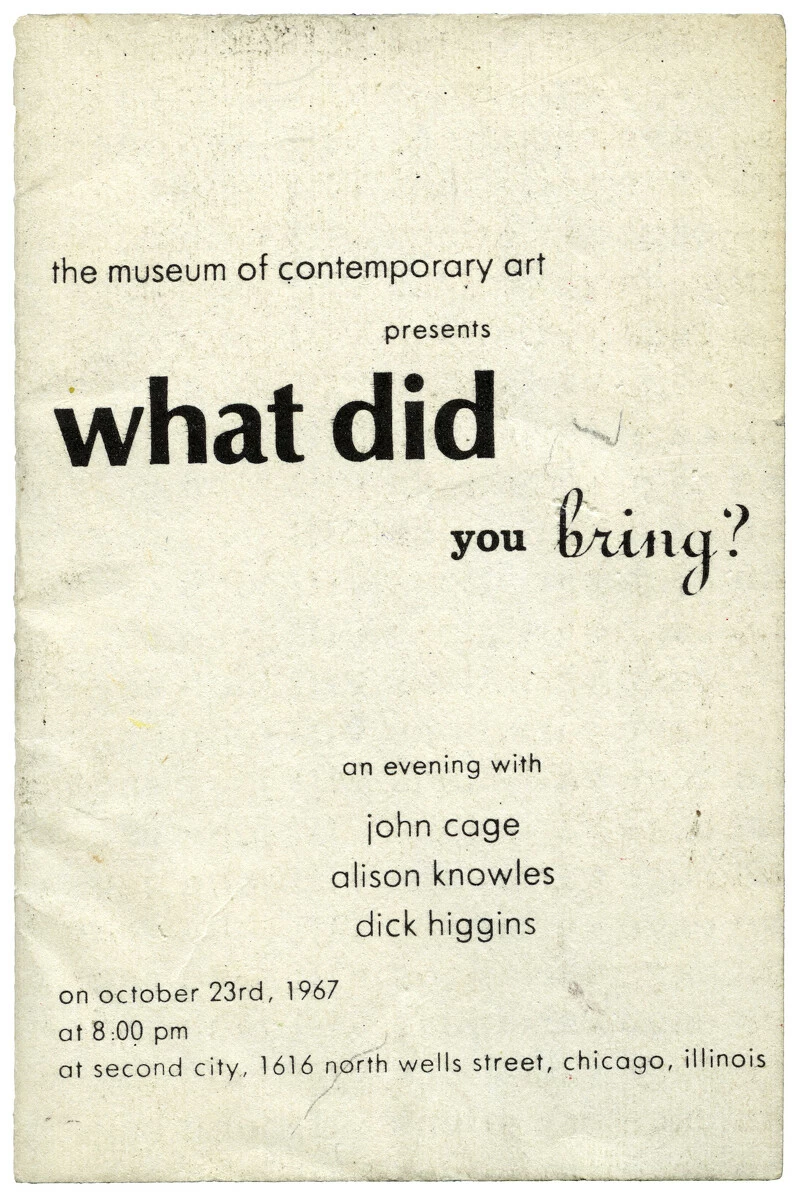

In a format that would become a fixture of the MCA’s early program, the performative thrust of the exhibition was rounded out with a live event titled What did you bring?, featuring performances by Knowles, Dick Higgins, and Cage, their former teacher (fig. 2). The evening unfolded offsite at Second City, an improv comedy club founded in 1959, to an invite-only audience. In what might be described as an exploded, theatricalized version of The Big Book, Knowles presented “a series of events employing projection systems, large quantities of vegetables, daily papers, string, and numerous other props,” while Cage cooked mushrooms on a hotpot. Later, Higgins performed one of his Graphis works, a series of nearly 150 notations providing prompts for action or movement. Informed by Higgins’s interaction with postmodern dancer Simone Forti, these works bridged the logics of drawing and choreography.[13] What did you bring? thus expanded Pictures’ interdisciplinary theme to the realm of live events, suggesting that the performative qualities of the art displayed in the galleries extended beyond the delimited space of the objects themselves. The making of performance, the museum asserted, ran parallel to the production of physical objects. And to understand such objects, one must look equally to new performance-based modes of making.

Illinois Central

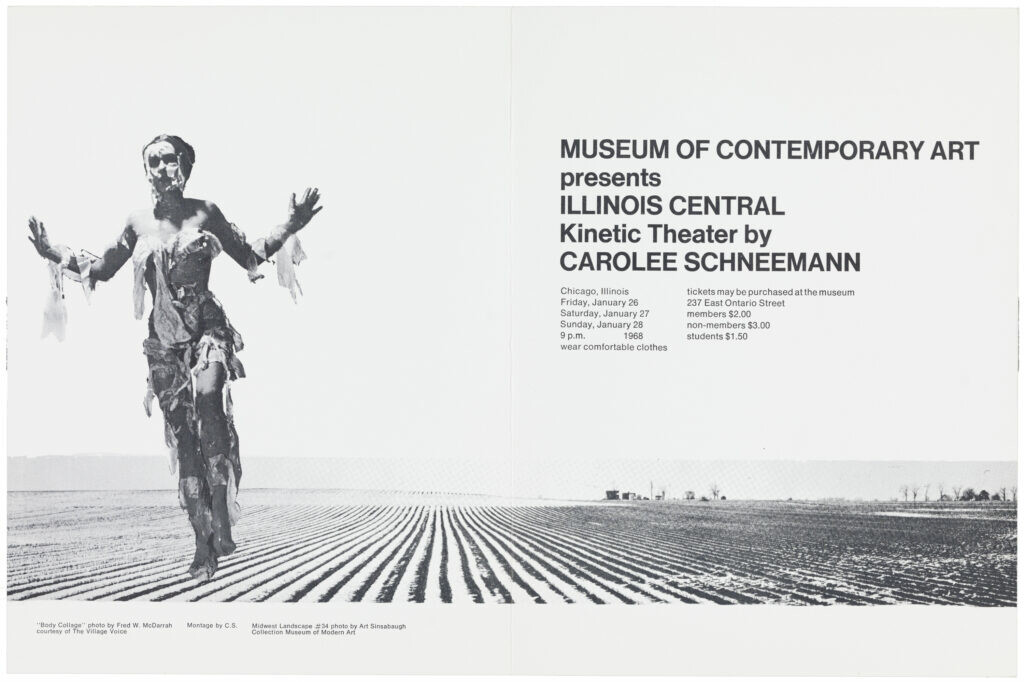

This two-part format—an exhibition thematizing performance practices and a live performance event—would not only become a hallmark of Van der Marck’s brief tenure at the museum, but would also provide the impetus for several important performance commissions. A year after the museum’s opening, the MCA invited Carolee Schneemann, an artist known for her work in “kinetic theater,” to debut a new work titled Illinois Central (fig. 3) in conjunction with an exhibition devoted to works made with paper.

Figure 3. Exhibition announcement for Carolee Schneemann: Illinois Central, MCA Chicago, January 26–28, 1968.

The performance was inspired by the flat stretches of Illinois’s landscape, familiar to Schneemann from her time as an MFA student at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign where she made her first “landscape environments” in 1961.[14] Here, her use of paper, the stuff of trees, came to stand in for their absence in such landscapes.[15]

Over the course of the 90-minute event, eight performers doused themselves in wallpaper paste and used it to wrap themselves head to toe in paper, including “bales of canceled bank checks,” transforming their bodies into paper “cocoons.”[16] They wove in and out of the seated audience, recruiting willing participants in a multi-sensory environment comprised of overlapping bodies, projections of landscape images, and the sounds of animals recorded at the Lincoln Park Zoo.[17] “I think of this work as an exploded canvas,” Schneemann later wrote. “Units of rapidly changing clusters. A flow of energy which makes an active audience inevitable and necessary—not to mimic the performance but to absorb relations within the space and between one another.”[18]

While Illinois Central drew on the image of its midwestern setting and enlisted a local audience, its political ambitions were global in scope. In keeping with Schneemann’s 1967 performance work Snows and the 1962–67 film Viet-flakes (a collaboration with James Tenney), Illinois Central took aim at the violence and devastation taking place in Vietnam. Deploying the tactile qualities of paper, the work staged a “visual paradox” between the barren landscape and the thrashing of mummified bodies, between the tranquility of nature and the violence of war. Meanwhile, its use of cancelled currency linked the destruction of trees and bodies, fusing local culture and capital to the politics of the world stage. By commissioning such work, the MCA not only demonstrated its investment in performance-based practices; it also underscored the capacity of such practices, and of contemporary art broadly, to address the era’s most pressing socio-political issues.

Decade’s End

By the time Van der Marck announced his retirement from the MCA directorship in June 1970, Knowles, Higgins, Cage, and Schneemann represented a fraction of the expansive roster of avant-garde artists whose performances helped to introduce Chicago audiences to the phenomenological art of the 1960s and to what Rosenberg called the “Esthetics of impermanence.”[19] Such priorities had also continued to shape the exhibition program. In 1969, the museum debuted Art By Telephone, an exhibition inspired by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s claim that his so-called “Telephone Pictures” were produced by an enamel factory after he provided instructions over the phone.[20] Riffing on this 1920s precedent, the museum invited a group of 39 largely New York–based artists to dictate new works to be executed from afar by MCA staff members.

Here too, the art displayed in the galleries was accompanied by live events, in this case, an in-gallery program titled Mixed Media in which Fluxus artists Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik performed works by Paik, Cage, and Yoko Ono. Art By Telephone coincided with a retrospective of its catalyst and forebear, Moholy-Nagy, a choice reflective of a tension that would continue to define the institution’s identity in the years to come. On the one hand, the museum continued to prioritize the cutting-edge (often performance-based) work of living artists—a commitment that was facilitated by its founding model as Kunsthalle—while, on the other hand, it engaged in a parallel effort to legitimize such practices through retrospective exhibitions of historical artists, an approach more in line with the aims of collecting institutions.

Toward a Collecting Institution

With Van der Marck’s departure in 1970 came a moment of transition. Without his leadership, the MCA’s commitment to centering performance within the broader fabric of contemporary cross-media experimentation faded momentarily to the background. When performance eventually returned in full force, it came at a surprising moment—on the heels of the museum’s decision in 1974 to begin formally collecting works of art. As the institution shifted away from its founding Kunsthalle model, and its curators devoted new attention to acquisitions, performance found an unlikely champion in a young woman named Alene Valkanas who was hired in 1972 as the Museum’s Director of Public Relations.

Valkanas had an unusual trajectory, having spent the ages of 15 to 30 in a convent where she worked as a nun, teaching art and English. “I find art like a religion,” she explained of her decision to work in museums. “It’s a thing of the spirit and something you can believe in.”[21] She was hired soon after completing a master’s in education at the University of Chicago and at a time when the museum was still learning how to get people through the door. When they realized that events might function as a form of publicity and a means of cultivating their audience, they tasked Valkanas with organizing member programs, a role that would expand over the subsequent decade.

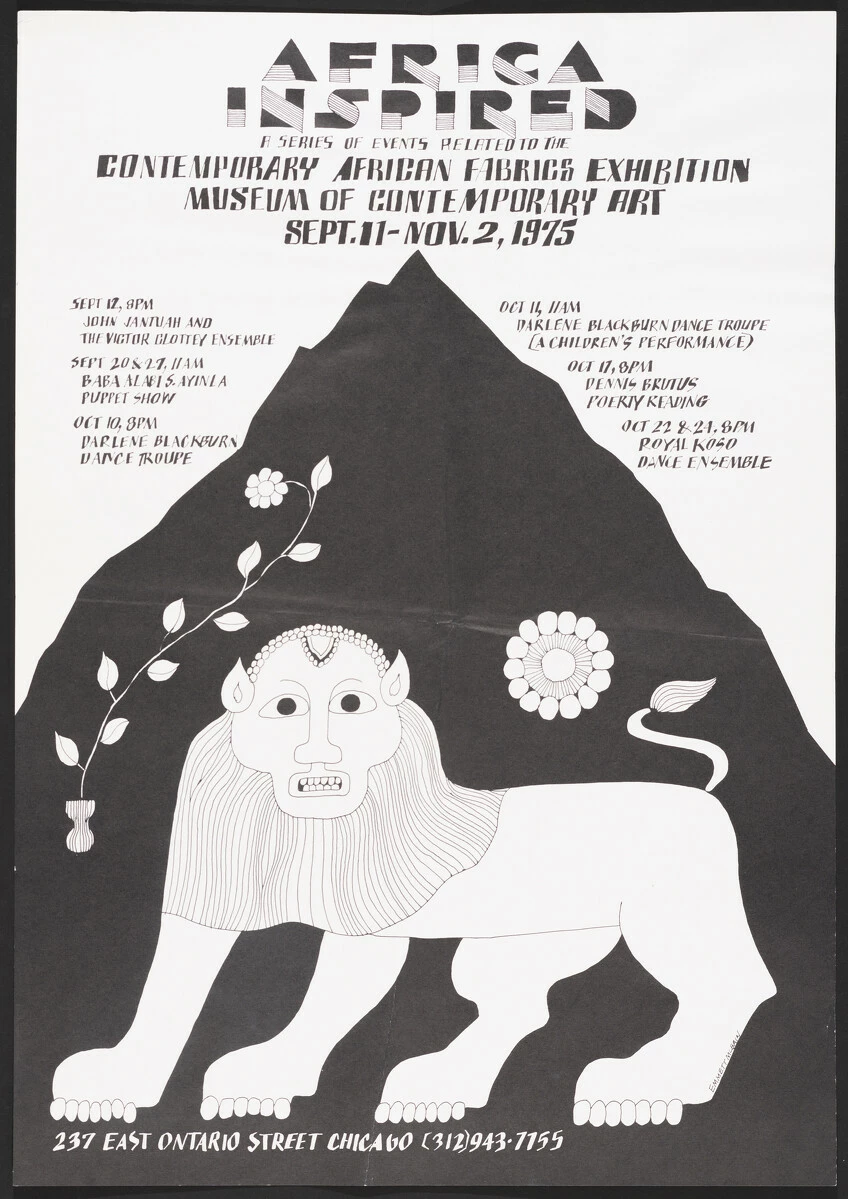

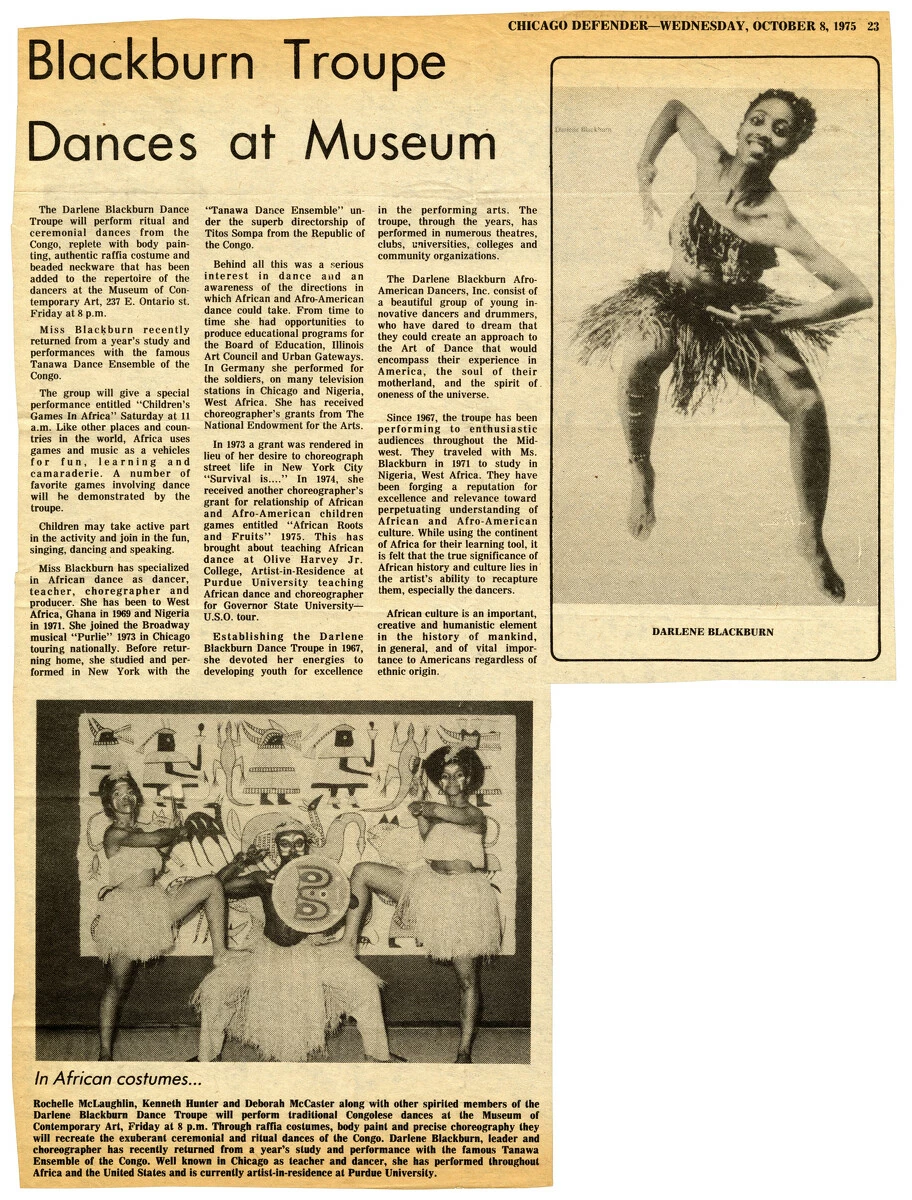

Whereas Van der Marck’s approach to performance grew out of his interest and training in the rarified world of contemporary art, Valkanas’s unconventional background and position in the museum meant that she embraced a more expansive view of performance-based practices. Under her leadership, the category broadened, becoming more flexible; it came to include more popular forms of artistic practice, including experimental music, theater, and dance. Her first concert, presented in 1973, featured the experimental jazz musician (and former Chicago resident) Anthony Braxton. In 1972, she programmed the first of many performances by the Darlene Blackburn Dance Troupe, a Chicago-based company of African American modern dancers who presented works inspired and informed by Blackburn’s travels to Nigeria, Congo, and other parts of West Africa (figs. 4,5).[22]

Valkanas’s approach to diversifying the performance offerings worked in several different directions. In one sense, it meant that artists of color who had historically been excluded from the museum’s exhibition program were suddenly offered another, albeit more impermanent, avenue for inclusion and exposure. It also meant that the museum made gains in attracting the broader audience it aimed to cultivate. “They were pleased to have these kinds of programs offered because it expanded their audience,” Valkanas later reflected.[23] At the same time, such developments represent an early instance of a pernicious tendency that continues to inflect museum programs—one in which the work of non-white artists is presented in conspicuously public ways. This approach, as Gordon Hall has perceptively noted, tends to position artists “as examples of their demographics, publicly displayed in an effort to signal the changing priorities of institutions that have been historically terrible at investing in the careers of female, non-white, and non-cisgender artists.” And because these modes of inclusion are often ephemeral, they “do not actually reflect a lasting curatorial and financial investment in an artist’s practice.”[24]

In the 1970s, artists like Braxton and Blackburn made repeated appearances in the MCA galleries, but their virtual absence in its archive raises important questions: how does a museum trace the history of performance when its primary mode of preservation revolves around objects rather than bodies? How does a museum account for the historical presence of non-white artists when their primary mode of inclusion resisted such forms of institutionalization?[25]

Bodyworks

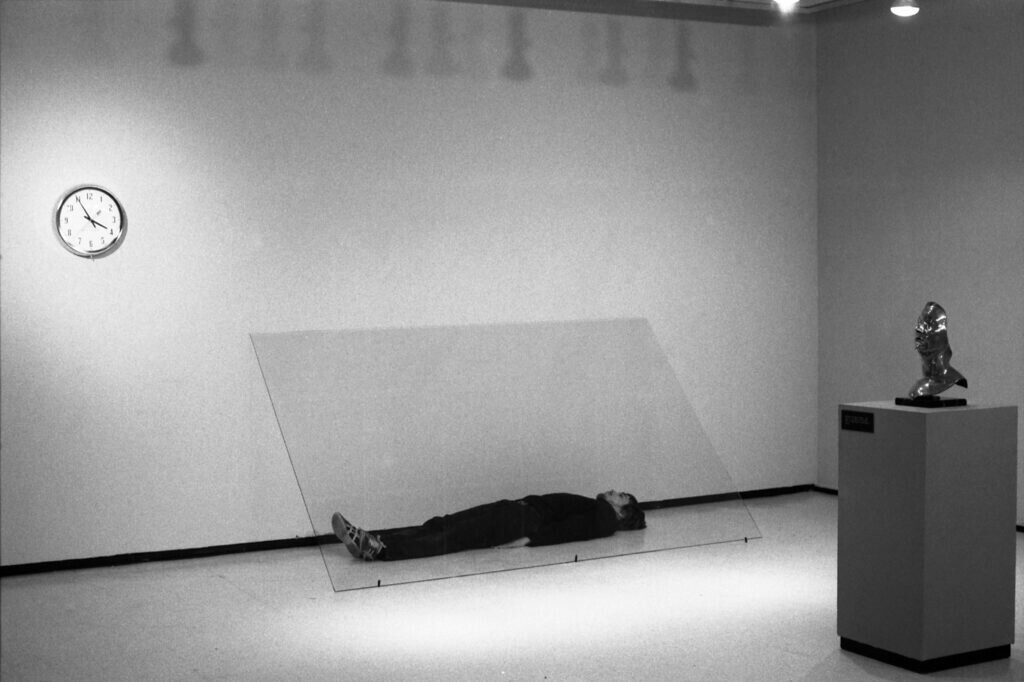

By the middle of the decade, the growing centrality of performance to many contemporary visual art practices also came to shape the MCA’s exhibition program, much as it had in the museum’s opening years. The shift was best reflected in the 1975 exhibition Bodyworks, organized by curator Ira Licht (fig. 6). Featuring artists such as Vito Acconci, Eleanor Antin, Chris Burden, Bruce Nauman, Dennis Oppenheim, and Adrian Piper, among others, the exhibition attempted to carve out a distinct domain of contemporary practice beyond the categories of happenings, dance, and the broader category of performance art. This new category of work, Licht argued, was “primarily personal and private. Its content is autobiographical, and the body is used as the very body of a particular person rather than as an abstract entity or in a role.” Bodyworks artists might create “performance situations,” or “admit audiences,” he explained, “nevertheless, the content of the performance is intimately involved with the artist’s psychological condition and personal concerns.”[26] These works, in other words, were tethered to particularity—they depended on and were anchored by the artist’s experimentations with his or her own physicality.

Figure 6. Installation view of Bodyworks, MCA Chicago, March 8–April 27, 1975. Photo © MCA Chicago.

As in the museum’s opening exhibitions, Bodyworks paired art displayed on the gallery walls with a series of four live performances undertaken by Laurie Anderson, Acconci, Oppenheim, and Burden. In Doomed, Burden rested on the gallery floor beneath a large sheet of glass that leaned against the wall at a 45-degree angle. To foreground the museum’s role in the making of the work, Burden determined that Doomed would end when the institution interfered in this tableau. “I thought—OK, I’ll start it, you end it,” he later reflected.[27] Though Burden expected the performance to conclude before the end of the day when the museum was scheduled to close, MCA staff members were unaware of this expectation. Rather, believing that it was their responsibility to enable Burden’s durational performance, they kept the museum open (and the performance running). Doomed lasted for an astonishing 45 hours until one staff member, Dennis O’Shea, brought Burden water and unwittingly brought the performance to its end (fig. 7).[28] Despite the miscommunication, this sequence of events reflects the museum’s commitment to prioritizing the needs and vision of living artists. Performances like Doomed were possible because of dedicated staff members—security guards, installers, and administrators—who were themselves often practicing artists, and who worked collaboratively and creatively to realize complex and at times unpredictable projects.[29]

Figure 7. Chris Burden performing Doomed during the MCA exhibition Bodyworks, 1975. Photo © MCA Chicago.

Whereas the live performances offered unmediated access to the physicality of the performers’ bodies, the gallery presentation of Bodyworks was documentary in nature, featuring the mediated (often photographic or filmic) trace of past actions. Piper, for example, was included with a series of six black-and-white photostats belonging to her Mythic Being series, in which she performed in the New York City streets disguised as a man. In the photographic iteration of the work displayed at the MCA, viewers encountered Piper’s washed-out, nearly silhouetted image set against a black background and accompanied by text taken from her journal and reproduced in a thought bubble. Such works wielded the intimacy of private thought to bring white viewers into public awareness of their racial and gender-based assumptions. Here and in the works by other Bodyworks artists, past performance formed the basis for a new kind of encounter in the present. By showing such works, the MCA offered yet another view onto a constellation of performance-based practices that ran parallel to and in this case, informed the making of the objects displayed on its walls.

Performance and Chicago

The growing centrality of performance to contemporary art—brought about by the intermingling of disciplines like experimental music, dance, and visual art—and its growing presence in museums and galleries in these years brought new infrastructural demands to institutions that were largely ill-equipped to present anything but objects or hanging works. Though the MCA had been presenting ad-hoc in-gallery performances since its opening, it was no exception to these infrastructural challenges. By the mid-1970s it was no longer operating according to the flexible Kunsthalle model it first embraced. It now had a collection to care for and insure, a fact that necessitated closer attention to museum security and made the MCA disinclined to take on the added risk associated with staging events in valuable art objects’ vicinity. “The museum understood the limitations of the space,” Valkanas later observed. “As the years went on it became more and more aware of how difficult it was to present performance in a gallery where installations were being presented.”[30] At the same time, museum galleries were often not well-suited to the kinds of performance-based work artists were making, which might require theatrical lighting or floors suitable for dancing.[31]

In 1975, Valkanas instituted a novel work-around to the museum’s growing security concerns, proposing that it host daily performances in the one-to-two-week period in January when the museum was between exhibitions and the galleries sat empty. These January intermissions became a kind of flexible forum for the burgeoning Chicago performance community, offering an intensive if informal program of performances and discussions that featured touring and local artists—a laboratory for emerging artists, including students in the newly founded performance department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. If Valkanas’s earliest programs were designed to appeal to a broad and diverse public, this series signaled her new proximity to the more specialized world of contemporary art, and within that, the city’s niche community of artists working in performance.[32]

Valkanas’s ability to position the MCA as a hub for experimental performance was made possible by her growing ties to the network of avant-garde performance in New York and Los Angeles. In 1976, she made the acquaintance of Jane Crawford, the founder and agent behind Art Performances, INC, a new nonprofit organization that filled a gap left by galleries in supporting institutions and individuals who wanted to present artists working in performance. Crawford’s brochures offered an introduction to some of the day’s most cutting-edge artists, including Constance de Jong, Tina Girouard, Julia Heyward, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Charlemagne Palestine, among others. She provided information about their practices, documentation of work, logistical needs and preferences, touring schedules, availability, and even proposals for the presentation of specific performances.[33]

Figure 8. Meredith Monk performing at MCA Chicago, 1977. Photo © MCA Chicago.

Crawford’s presence in this story brings two things into focus: on the one hand, the evolving status of performance within the contemporary art ecosystem—including the need to find new ways of supporting such practices—and, on the other hand, the crucial role played by women in meeting such needs. As Jenni Sorkin has noted, women artists were largely responsible for the development of Chicago’s performance culture, establishing alternative spaces equipped to accommodate such work.[34] Though the MCA represented a mainstream venue for art, Valkanas was nonetheless a crucial piece of this city-wide picture, using her institutional platform to establish local partnerships and collaborations, and often championing the work of women artists. With Crawford’s support, she instigated return performances in 1977 by Laurie Anderson and Meredith Monk, then little-known pioneers of multidisciplinary experimental music (fig. 8). Staged a month apart, both performances took place through an National Endowment for the Humanities–funded collaboration with the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Twentieth Century Studies, a burgeoning midwestern hub for performance studies.[35] Later that same year, in the wake of performance by Anderson and Monk, Valkanas orchestrated a co-sponsored lecture/demonstration with postmodern choreographer Trisha Brown at the School of the Art Institute.

These connections were crucial for maintaining and developing performance at the MCA while the institution simultaneously left its Kunsthalle origins behind. As the museum navigated the presentation of performance in the context of its newly established collection, it depended on forms of thinking and working that extended beyond the confines of its walls. Valkanas’s success in contributing to a thriving performance community in these years hinged on her talent for forging creative partnerships and non-traditional modes of programming and stewardship.[36]

Performance Week

Though in its first decade the museum presented a range of exhibitions thematizing performance-based practices as well as public programs featuring live performance, it did not stage a standalone performance exhibition until the late 1970s. This was in part a function of the developing state of performance art, an evolving and somewhat nebulous category of practices that emerged simultaneously.

With the rise of the conceptual practices in the 1960s came a suspicion and critique of the art object, the museums that house them, and the art world’s commercialism. Artists turned instead to various more ephemeral modes of critique, deploying a host of strategies aimed at what Lucy Lippard called the “dematerialization of the art object.”[37] Such practices spanned artistic movements—traversing Minimalism, Conceptual Art, Fluxus, postmodern dance, Body Art, and Institutional Critique—as well as the disciplines of theater, music, and dance. Presenting, contextualizing, and naming such slippery contemporary trends was no easy task. At the MCA, it was further complicated by the museum’s own shifting priorities and, importantly, by its decision in 1974 to transition from the Kunsthalle model to a collecting institution, devoted at least in part to the preservation of valuable objects.

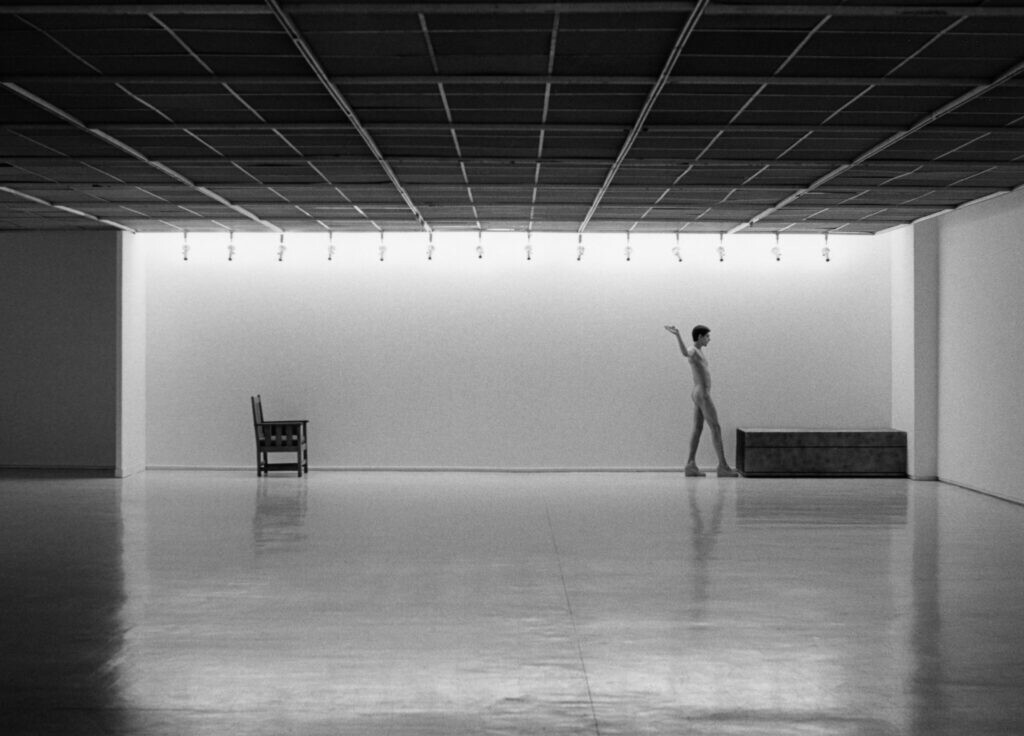

In the span of a decade, however, the museum had come to define multiple avenues for presenting performance, moving between public programs highlighting the performing arts to new developments in the domain of visual art performance. In 1977, a decade after opening its doors, it debuted “Performance Art Week,” an exhibition and showcase of contemporary trends in performance that capitalized on the format of Valkanas’s January intermissions (fig. 9). “Performance, the newest area of creative research in visual arts where the artist and what he does become the ‘art object,’ is too often only experienced through written documentation and analysis,” wrote MCA Director Stephen Prokopoff to Lewis Manilow, President of the MCA Board of Directors. “We are proud that the Museum is offering its public the rare opportunity to witness first-hand this new and evolving art form.”[38]

Figure 9. Scott Burton, Solitary Behavior Tableaux, 1977. Documentation of performance by Alfred Guido at MCA Chicago, 1977. Photo © MCA Chicago.

Over the course of a five-day period in the second week of January, the MCA hosted 22 performances and public discussions by six artists from New York, California, and Chicago. Echoing Pictures to be Read’s celebration of intermedial experimentation the decade prior, Performance Art Week underscored the “dissolution of the boundaries between the arts” and presented a broad range of contemporary approaches to performance, from “Scott Burton’s investigation into movement and its behavioral implications” to the “consciousness-raising work of Suzanne Lacy and the ritualized theater of Gunderson and Clark.”[39] Jared Bark presented vaudeville-style vignettes, Jon Hasell performed sculptural sound, and Thomas Kovacevich activated paper sculptures which shifted in response to variable atmospheric conditions. As this list suggests, the menu of performances underscored the broad range of practices that constituted the “evolving art form” of visual art performance.

For the first time since the museum’s founding, live performance had garnered a standalone exhibition, a fact that signals both the evolution of the field of visual art performance as well as the museum’s continued belief in its centrality to contemporary art writ large. Performance Art Week thus marked a subtle yet meaningful shift in the status of ephemeral performance within the institution. No longer merely adjacent or attendant to the display of objects, performance had become an independent, even anchoring force—or, as Prokopoff’s letter suggests, a new kind of “art object.”

Conclusion

The aesthetic tensions that characterized the MCA’s early performance history—between performing arts and performance art, live event and mediated representation, ephemerality and permanence—remain central to debates about where performance sits in the context of the contemporary museum. Such discussions often surface in the context of museum expansions in which opportunities to reevaluate architectural choices invite a parallel reconsideration of artistic needs and the kinds of theatrical spaces available—whether performance is to be integrated within the galleries, or siloed apart in a more distinctly theatrical setting. In the summer of 1978, the MCA embarked on a major renovation of its Ontario Street building, a project that was the impetus for four new commissions: Circus, or the Caribbean Orange, an exhibition by Matta-Clark in which he cut through the floors of the neighboring three-story townhouse; a related performance, “Spread,” by Tina Girouard in the same building’s ground-level window; a sound work by Max Neuhaus installed in the stairwell of the new building; and an installation by Michael Asher in which he manipulated decorative panels of the new museum’s exterior façade. In different ways, each of these projects might be understood as constituting a performance of sorts, some more or less obvious as such.[40]

In the months during which the museum remained closed, the museum’s director, John Neff, wrote to Valkanas reiterating his commitment to performance. “In short I think it is important that more be done to educate and interest our public in performance, dance, and contemporary music,” he urged. “We should be able to break some new ground for this in Chicago with a complete program of offerings, both actual performances and didactic ones.”[41] Though Neff recognized the full spectrum of practices and disciplines that constitute performance in the museum, and was committed to using the museum’s platform to bring such practices to Chicago audiences, his directive points to the fine-art hierarchies and distinctions that continued to haunt such ambitions. What is the difference, one wonders, between “actual” and “didactic” performances? And how do such distinctions map on to questions about target audience, artistic disciplines, and institutional resources?

Such questions are as relevant today as they were in 1978. In the intervening years, the MCA continued to expand, eventually moving in 1996 to its current building on East Chicago Avenue, a space that boasts a three-hundred-seat theater at its architectural core. While the theater made possible the kinds of performance productions that depend on the proscenium stage format and related resources, it also, perhaps unwittingly, introduced a new degree of separation between the performing and visual arts, a distinction further exacerbated by the growth of the museum’s collection. At a time when the Kunsthalle chapter of the museum’s history feels like a distant past, what might it look like to recuperate some of that moment’s slippery sites of overlap between performance and visual art? How might the museum continue to program performance in close dialogue with exhibitions and collect in concert with performance?[42] After all, these domains weren’t always floors apart.

Notes

I would like to thank the many current and former MCA staff members who spoke to me and helped to facilitate my research: Nolan Jimbo, Jamillah James, Claire Renaud, Iris Colburn, Jack Schneider, Jadine Collingwood, Bana Kattan, Cecilia González Godino, Joey Orr, Carla Acevedo-Yates, Laura Paige Kyber, Leah Singsank, Tara Willis, Lynne Warren, Peter Taub, Judith Russi Kirshner, and especially Mary Richardson who is a vast trove of knowledge about the MCA’s history and who provided crucial guidance in navigating its archival holdings. Thanks also to Elijah Teitelbaum for his editorial care.

1. See, for example, Claire Bishop, “The Perils and Possibilities of Dance in the Museum: Tate, MoMA, and Whitney,” Dance Research Journal 46, 3 (2014): 63–76.

2. See “The Reality of a Dream,” a museum publication outlining the Museum of Contemporary Art’s mission at the time of its founding, n.p. MCA Chicago Collection of Development Publications, 1968-present, Box 1, Folders 1-4, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Library and Archives.

3. “The Reality of a Dream,” n.p.

4. Alfred H. Barr, quoted in Charlotte Klonk, Spaces of Experience: Art Gallery Interiors from 1800-2000 (Yale University Press, 2009), 212.

5. Pictures to Be Read was on view when the museum opened in October 1967. Two Happening Concepts: Allan Kaprow and Wolf Vostell opened on November 28, 1967. The museum also organized actual happenings by both artists. Kaprow’s work Moving took place across six offsite locations between November 29 and December 2. Vostell’s performance of Concrete Traffic took place in January 1970. In April of that year, the museum also arranged a second interactive event: “By special arrangement, the molds from Wolf Vostell’s ‘Concrete Traffic’ event of January could be rented to any member who would like to transform the basic contours of the car into those of a 1957 Cadillac. See “MCA Performance and Program History 1967-1979,” chronology, Performing Arts Events Archive, 1967-1982. Museum of Contemporary of Art Chicago Library and Archives.

6. “Museum of Contemporary Art Opens Doors With ‘Pictures to Be Read/Poetry to Be Seen,’” press release (undated), Pictures to be Read/Poetry to be Seen Exhibition Records, Box 1, Folder 1, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Library and Archives.

7. Jan van der Marck, “Introduction,” Pictures to Be Read / Poetry to Be Seen (The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 1967).

8. Van der Marck, “Introduction.”

9. Ina Blom, The Name of the Game: Ray Johnson’s Postal Performance (Oslo: National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2003).

10. In framing these works in the language of “intermedia,” Van der Marck drew on the work of Fluxus artist Dick Higgins who was also included in the exhibition. A hand-written note on his primary sources notes, “Dick Higgins, Fluxus was very important.” Jan van der Marck Papers, The Museum of Contemporary Art Archives, Chicago. The note also cites two exhibitions: Jasia Reichardt’s 1965 Between Poetry and Painting at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Arturo Schwarz’s 1967 exhibition, Towards a Cold Poetic Image at Galleria Schwarz, Milan.

11. Harold Rosenberg, “Museum of the New,” New Yorker, November 18, 1967.

12. Van der Marck, “Introduction.” (emphasis mine)

13. On Higgins’s Graphis series, see Bonnie Marranca, “Lines of Thought: The Graphis Series of Dick Higgins,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 36, no. 2 (2014).

14. “The Museum of Contemporary Art Presents Kinetic Theatre January 26 and 27,” press release, January 15, 1968, Performing Arts Events Archive 1968-1983, Box 3, folder 12, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Library and Archives.

15. The program for the evening stated: “‘Illinois Central’ is an exploded canvas, a metaphorical arena of sensory juxtapositions. The central image of this pieces is The Tree; the absence of the tree as characteristic of Mid West landscape and the transformation of the tree into paper.” Performing Arts Events Archive 1968-1983, Box 3, Folder 12, Museum of Contemporary Art Archives Chicago Library and Archives.

16. Sabine Breitwieser, Branden Wayne Joseph, Mignon Nixon, Ara Osterweil, Judith F. Rodenbeck, and Carolee Schneemann, Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Painting, translated by Gerrit Jackson (Museum der Moderne and Prestel, 2015), 194, 196.

17. Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Painting, p. 196. Viet-Flakes, a collaboration with James Tenney, was projected on the central wall of the performance space as the performers exited.

18. Carolee Schneemann, quoted in Carolee Schneemann: Kinetic Painting, 194.

19. This list includes Pauline Oliveros, Allan Kaprow, Meredith Monk, Wolf Vostell, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Whitman, and Christo; and Harold Rosenberg, quoted in Rebecca Zorach, “Making Space 1961-1976,” in Art in Chicago: A History from the Fire to Now, edited by Maggie Taft (University of Chicago Press, 2018), 221.

20. Van der Marck owned the smallest of the three enamel paintings, titled EM 1 (1923). The work was purchased from its subsequent owners in 2016 by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. See: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/147626.

21. “From Nun To PR Director,” The Oil City Derrick, Monday, October 23, 1972.

22. Reporting on the troupe’s 1975 appearance in the museum, the Chicago Defender wrote: “The Darlene Blackburn Dance Troupe will perform ritual and ceremonial dances from the Congo, replete with body painting, authentic raffia costume and beaded neckware.” “Blackburn Troupe Dances at Museum, Chicago Defender, October 8, 1975.

23. Dominic Molon, interview with Alene Valkanas, The Illinois Arts Alliance, July 28, 1995, Alene Valkanas Papers, Box 1, Folder 4, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Library and Archives.

24. Ibid.

25. Such questions have been productively taken up in the field of Performance Studies by scholars such as Diana Taylor and Rebecca Schneider. Taylor articulates such tensions in terms of the distinctions between the “archive” and the “repertoire”: “The rift, I submit, does not lie between the written and spoken word, but between the archive of supposedly enduring materials (i.e., texts, documents, buildings, bones) and the so-called ephemeral repertoire of embodied practice/knowledge (i.e., spoken language, dance, sports, ritual).” Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: performing cultural memory in the Americas (Duke University Press, 2003), 19. In the context of museums generally and the MCA specifically, we might ask what it would look like for the archive and the repertoire—the museum’s collection as well as its embodied, relational histories—to be valued equally. Thank you to Joey Orr for his productive discussions on this point.

26. Ira Licht, Bodyworks (MCA Chicago, 1975), n.p.

27. Chris Burden, quoted in Cynthia Carr, “This is Only a Test: Chris Burden,” Artforum 28, no. 1 (September 1989).

28. Thanks to Mary Richardson and Elijah Teitelbaum for clarifying this sequence of events. See https://mcachicago.org/publications/blog/2015/05/in-support-of-uncertainty-chris-burdens-doomed.

29. Thank you to Judith Kirshner for drawing my attention to this “artist-first” aspect of the museum’s culture in these years.

30. Interview with Alene Valkanas.

31. Blackburn’s troupe was an outlier in the realm of dance, which often requires a sprung floor. For the most part, this limitation meant that Valkanas rarely programmed dance events in these years. See interview with Alene Valkanas.

32. The MCA’s January “intermissions” constitute an important precursor to the Renaissance Society’s current Intermissions program, launched in 2017 and “devoted to performance and other inventive time-based works, staged in the Renaissance Society’s empty gallery in between exhibitions.” See, for example: https://renaissancesociety.org/events/1346/intermissions-alexandra-pirici/.

33. “Tina prefers working with people from the area of the performance location and involving them in the performance,” Crawford wrote of Girouard. The same letter notes an enclosed proposal by Matta-Clark. Both artists would make important appearances at the MCA in 1978. Jane Crawford, letter to Alene Valkanas, November 16, 1977, Performing Arts Events Archive 1967-1982, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Library and Archives.

34. Jenni Sorkin, “Alterity Rocks,” in Art in Chicago: A History from the Fire to Now, 258.

35. In a letter negotiating these co-sponsored programs with the Center’s director, Michael Benamou, Valkanas wrote: “I would very heartily like to suggest Laurie Anderson. Last year with little advance notice and virtually no reputation in Chicago, she gave a most powerful performance during our Bodyworks exhibition.” Benamou agreed. Alene Valkanas, letter to Michael Benamou, January 14, 1976, Performing Arts Events Archive, 1967-1982, Box 3, Folder 13, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Library and Archives.

36. It is perhaps not surprising to note that it was primarily women artists and queer communities who were instigating these alternative ways of working. Thank you to Mary Coyne for pressing me to think deeper on the points articulated in this section.

37. See Lucy Lippard, Six Years: the dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972 (Praeger, 1973).

38. Stephen Prokopoff, letter to Lewis Manilow, April 1, 1977, Performing Arts Events Archive 1967-1982, Box 3, Folder 14, Museum of Contemporary Chicago Library and Archives.

39. “Performance Art,” press release, December 22, 1976, Performing Arts Events Archive 1967-1982, Box 3, Folder 14, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Library and Archives.

40. Judith Russi Kirshner, curator at the MCA from 1976 to 1981, aptly refers to these commissions as “performance as process.” Email with the author, December 3, 2024.

41. Note from John Neff to Alene Valkanas, September 8, 1978, Performing Arts Events Archive 1967-1982, Box 3, Folder 25, Museum of Contemporary Art Archives Chicago Library and Archives.

42. One productive response to such questions can be found in the MCA’s 2018–19 exhibition Groundings organized by Grace Deveney and Tara Aisha Willis, which considered the reciprocal ties to movement posed by objects and embodied practices. The exhibition staged a transdisciplinary conversation among works in the museum’s collection and a series of live programs featuring performers-in-residence.

About the Author

Jenny Harris is a writer, curator, and doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago. Her research explores global modernism with interests in the relationships between abstraction and ornament, dance and visual art, and craft and design. Her writing has appeared in several exhibition catalogues, Artforum, and The New York Times. She has worked as a curatorial assistant in Painting and Sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art and as a research fellow in Modern and Contemporary Art at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Funding

The MCA DNA Research Initiative is supported by the CHANEL Culture Fund.