Bani Abidi: The Man Who Talked Until He Disappeared

Sep 04, 2021 - Jun 05, 2022

About the Exhibition

In Bani Abidi: The Man Who Talked Until He Disappeared, Pakistani artist Bani Abidi (b. 1971, lives and works in Karachi and Berlin) critiques those who hold power—and the many ways they wield it. Abidi is a master storyteller, using humor and absurdism to take on issues of militarism and nationalism as well as memory, belonging, and self-determination. Like an archaeologist of urban life, Abidi intermingles fact with fiction in stories that navigate the intersection of personal and political drama. This major survey, developed in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation, explores more than two decades of Abidi’s practice and features video, photography, sound installations, and new work, as well as work from the MCA Collection.

The MCA presentation is curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, President and Director of Sharjah Art Foundation; Natasha Ginwala, Associate Curator at Gropius Bau, Berlin; and Bana Kattan, Pamela Alper Associate Curator.

Curators’ note

Pakistani artist Bani Abidi lampoons the languages of power and their diverse manifestations in nationalism, militarization, state surveillance, and gender norms. Featuring formative video, photography, and sound works as well as new commissions, this major survey explores the artist’s practice over two decades and includes work from the MCA Collection. Playing the role of a storyteller and urban archaeologist, Abidi delves into an emotional and psychological space of satire, absurdity, and social commentary. In this exhibition developed in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation, the artist’s works are imbued with personal and communal narratives impacted by current geopolitical relations between India and Pakistan, the historical power struggles of South Asia, and the local impact of interventionist American operations in the wider region. From the specific social and political context of Pakistan, she wrestles with the collective amnesia of a cosmopolitan promise that has been erased by nativist populism as well as ideological and sectarian nationalism that also encroaches upon struggles for justice around the world.

The artist performs to the camera in her earliest video works made while she was a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. These role-plays that figure Indian and Pakistani protagonists mine the history and current political tensions between the two neighboring states through whimsical, comparative analysis of food, music, and news media. These works manifest divisions within the popular imagination, while revealing deep affinities that transgress borders. In later works, disciplined and defiant bodies confront visible and invisible spectrums of power. Everyday life must navigate immigration protocol, road closures, and taxonomies of security barricades. The dramaturgy that animates much of Abidi’s work blurs the distinction between screen time and real time, actors and non-actors, scripted and spontaneous moments.

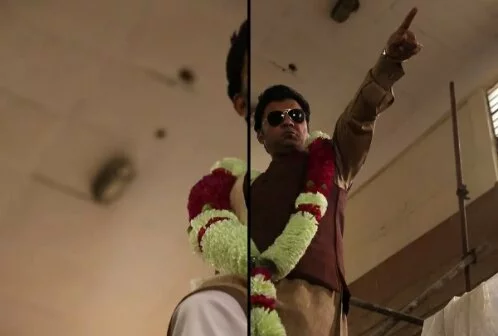

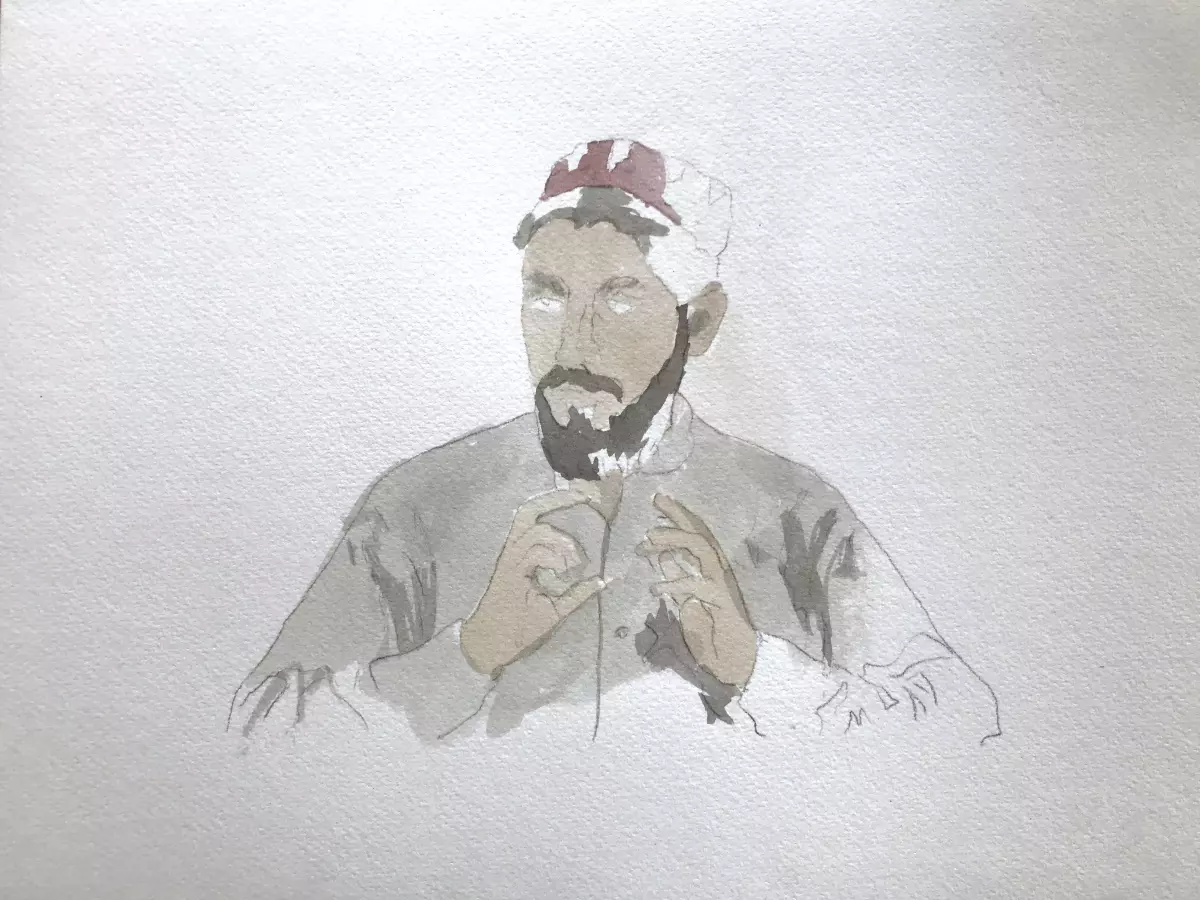

For this exhibition, Abidi expanded the watercolor series The Man Who Talked Until He Disappeared (2019–ongoing) that engages with the memory of writers, political leaders, and bloggers across Pakistan who have disappeared over the past decade. Her new work, The Reassuring Hand Gestures of Big Men, Small Men, All Men (2021), features an affective archive of gestures and dispositions associated with masculinist leadership, such as charisma, comradeship, and patriotic fervor, which have been assembled from news media. Memorial to Lost Words (2017–18) offers a historically grounded reflection on memory and lamentation, pairing old Punjabi songs with confiscated letters written by South Asian soldiers to loved ones while fighting on behalf of the colonizing British during World War I. The work asks how the testimony of a beloved, South Asian solider in the trenches during the World War I speaks today as warring times persist.

This exhibition is an ensemble that acknowledges multiple forms of living in relation, moving across geographies while holding onto aspiration and desire. With dry wit and expert storytelling, Abidi gestures to how acts of defiance remain legible and embrace irony in her milieu—carving out pockets of liberation from scenes of dominance and forced homogenization.

This exhibition follows on from the artist’s solo survey exhibition Bani Abidi: They Died Laughing at Gropius Bau, Berlin, curated by Natasha Ginwala, which was on view from June 6 to September 22, 2019, and Bani Abidi: Funland at the Sharjah Art Foundation, which was on view from October 12, 2019 to January 12, 2020, cocurated by Hoor Al Qasimi and Natasha Ginwala.

Related Content

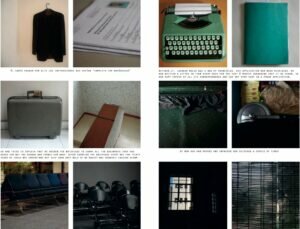

Two of Two

Section Yellow is an installation that features the video The Distance From Here, a vinyl-floor labyrinth titled Exercise in Redirecting Lines, and an accompanying poster titled Two of Two. Abidi staged a scene of people waiting, passing through metal detectors, and organizing within rows of chairs and yellow traffic lines. Her video captures the charged and dehumanizing experience of applying for a visa. Stacked on a pallet are takeaway posters that show the applicants’ belongings. Extending the features and choreographies of bureaucracy into the gallery, Abidi traced the video’s yellow traffic lines onto the floor, and also dotted the gallery space with the red physical barriers.

Mangoes, Transcript

[PLATES CLANKING, CHEWING]

SPEAKER 1: These mangoes are so huge. Not very good. They’re fairly tasteless.

Have you had Anwar Ratols? I don’t know what you call them in India, but, they’re small and have a very—really strong aroma. And we usually cut them. I mean, we usually suck them because they’re too small to cut. Those are my favorite ones.

It’s so funny. My mother used to always have an Anwar Ratol lying in her plate while she was eating her normal meal. And she’d take a bite of the mango, and a bite of her food. And I just could never understand it. You know, the concept of having a savory and sweet food together. So odd.

[PLATES CLANKING]

SPEAKER 2: You know, I remember all these afternoons in my grandmother’s house. All of us cousins used to get together in the afternoons after lunch, and have buckets of mangoes just piled up. And everyone, of course, would be just gorging down mangoes.

And this one cousin of ours who was a bit naive, my brother always used to tell her that the more you chew your gutli and the more you suck it clean, the more mangoes you’ll get. And of course, while she was doing it everyone would have her share, like, everyone would have three mangoes. With such nice memories attached to it. And very often it used to be raining.

I really always think of summer every time I have mangoes.

You know, my mother wanted to send me a crate of mangoes through this cousin of mine who’s coming here, and the customs people here, just don’t allow it. It’s such a disappointment.

SPEAKER 1: I know. I’ll hopefully be going home in August. So I’m hoping to get some good mangoes.

SPEAKER 2: So how many mangoes do you get in—sort of mangoes you get in Pakistan?

SPEAKER 1: I think we have about five, five main. What about India?

SPEAKER 2: I think we have about six.

SPEAKER 1: Actually, I think Pakistan also has six or seven different types.

Related Events

March 1, 2022

12:00 pm - 2:30 pm

Artist Talk | Bani Abidi

Funding

Major support is provided by the Zell Family Foundation, Cari and Michael Sacks, R. H. Defares, Charlotte Cramer Wagner and Herbert S. Wagner III of the Wagner Foundation, and Anonymous.

Generous support is provided by Murat Ahmed and Katherine Mackenzie, and by the Shulamit Nazarian Foundation.

This exhibition is supported by the Women Artists Initiative, a philanthropic commitment to further equity across gender lines and promote the work and ideas of women artists.