Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi مریم تقوی

Dec 20, 2023 - Jul 14, 2024

About the Exhibition

For the next iteration of its Chicago Works series, the MCA presents the first solo museum exhibition of artist Maryam Taghavi (b. Tehran, Iran; based in Chicago, IL).

Taghavi’s practice insists on positionality: where one stands determines what—and how—one sees. For the past several years, her work with talismans, calligraphy, and the Islamic occult has coalesced into a series of sculptures and paintings that strive to signify the unseen. In her MCA exhibition, Taghavi creates new works that expand her interest in perception by interrogating the space between the illusive vanishing point of the horizon and the immutability of distance.

Taghavi’s exhibition takes over the MCA’s Turner Gallery on the fourth floor, culminating in an immersive installation that invites audiences to close one eye and peer with the other, to adjust their gaze to new spatial possibilities, and to imagine a relationship with what is imperceptible.

Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi is organized by Bana Kattan, Pamela Alper Associate Curator, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, with Kamala GhaneaBassiri, Visual Arts Intern.

Maryam Taghavi is the 25th artist to be part of Chicago Works, a solo exhibition series at the MCA that features artists who are shaping the contemporary art scene both in the city and beyond. This exhibition is the first MCA exhibition to be fully translated into Persian.

About the Artist

Maryam Taghavi is an artist and educator born in Tehran, Iran, and a resident of Chicago. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts from Emily Carr University and Master of Fine Arts from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where she was the recipient of The New Artist Society Scholarship. Her art engages with a range of disciplines such as painting, drawing, sculpture, performance, publication, and installation. She has exhibited nationally and internationally at institutions such as LAXART, Queens Museum, Exterressa Museum, Chicago Cultural Center, and Driehaus Museum, among others. In 2023 her sculpture work was commissioned by the City of Chicago to be permanently installed at O’Hare International Airport’s Terminal 5.

Installation Images

Related Content

In this interview at her Chicago studio, Maryam Taghavi reflects on how calligraphy, the noghte, and the sculpture of Parviz Tanavoli relate to her work.

With English and Spanish closed captions

Exhibition Essay: Maryam Taghavi and a Choreography for Nothing

English

Maryam Taghavi and a Choreography for Nothing

BANA KATTAN

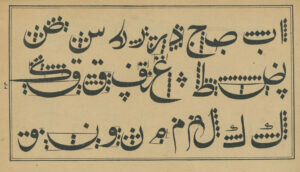

In Persian and Arabic, the noghte is the most essential diacritical mark. The number of noghte(s) that a writer places above or under a particular letterform indicates its sound: for example, the same letterform may become b, y, p, n, t, or th, depending on the noghte’s arrangement. Loosely translated into English as “dot” or “point,” in calligraphy this diacritic is etched from the slanted nib of a reed pen, creating a diamond-like form. In the early tenth century, a vizier to the Abbasid caliphs in modern-day Baghdad named Ibn Muqla developed a system for determining the size of letters in an alphabet based on the noghte. Muqla began by calculating the height of the first letter in the Arabic alphabet, the alif, based on the height of a series of noghte(s); he then determined the size of all other letters in relation to the alif[1]. Since Muqla’s invention of this “proportional script,” the noghte has been used as a unit of measurement for all spatial relations within a given calligraphic composition (fig. 1).

Figure 1. A 19th-century lithograph of script in the Naskh style, one of the earliest forms of Islamic calligraphy. Courtesy of Borna Izadpanah.

For artist Maryam Taghavi (b. Tehran, Iran; lives in Chicago, IL), the noghte is to literary culture “what the seed is to a tree. It’s impossible to think that this small unit is holding the blueprint for a whole tree, but it’s in there. And I think of the dot or the ‘noghte’ in the same way, that it’s like the entry to a whole world.”[2] In Taghavi’s solo exhibition at the MCA, Chicago Works: Maryam Taghavi, the noghte emerges as a central motif that influences both the construction of meaning and how one perceives distance. In the installation, paradoxically titled Nothing Is, Taghavi carefully utilizes elements of a visual culture that she grew up with, such as traditions drawn from Islamic calligraphy, Persian miniature painting, and Persian architecture. Taghavi’s treatment of these traditions is reverential, but it is also subtly irreverent. Using irony, abstraction, and transliteration, her work moves between the transcendental and the transgressive—a transition reflected in the space of the exhibition.

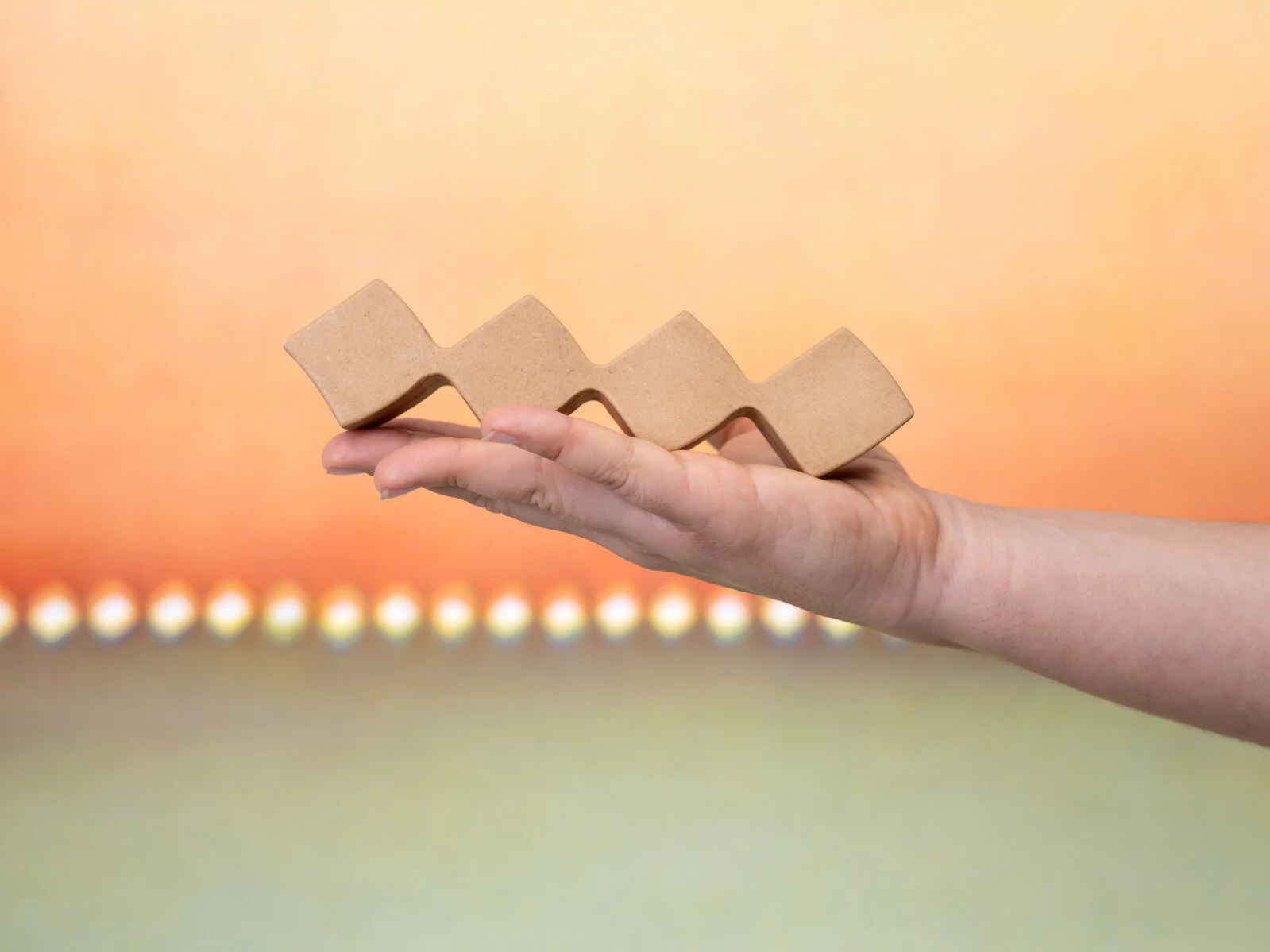

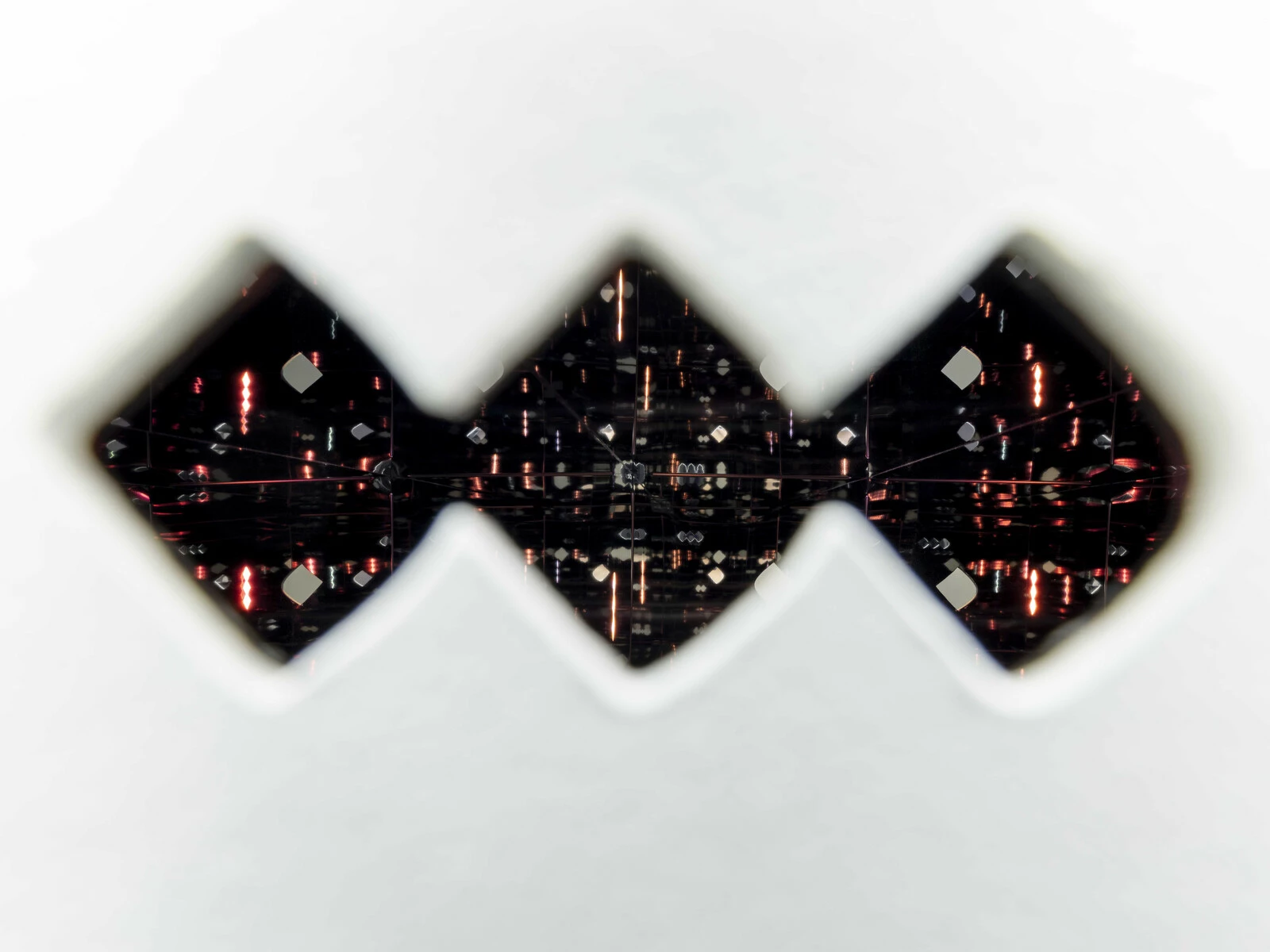

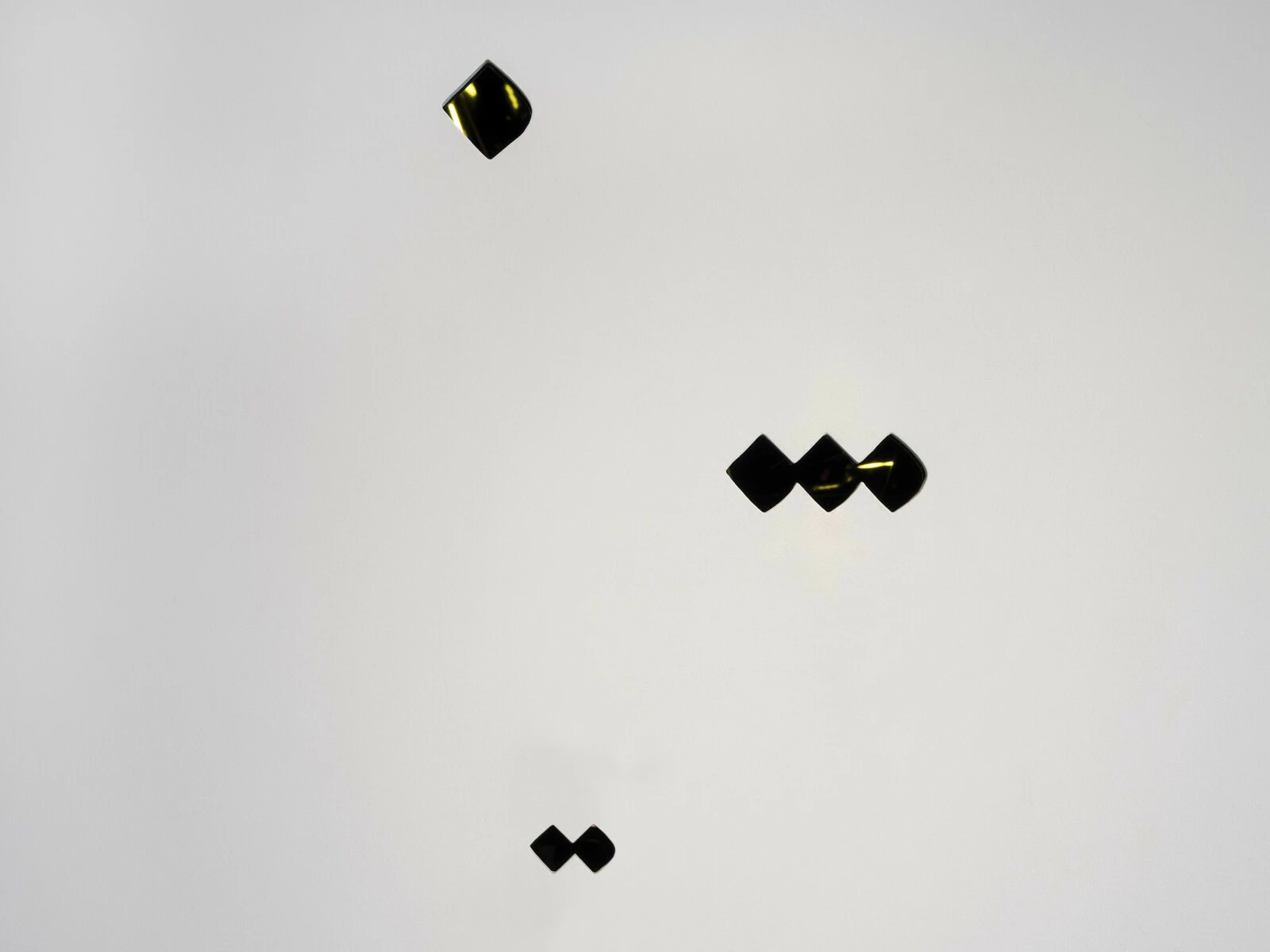

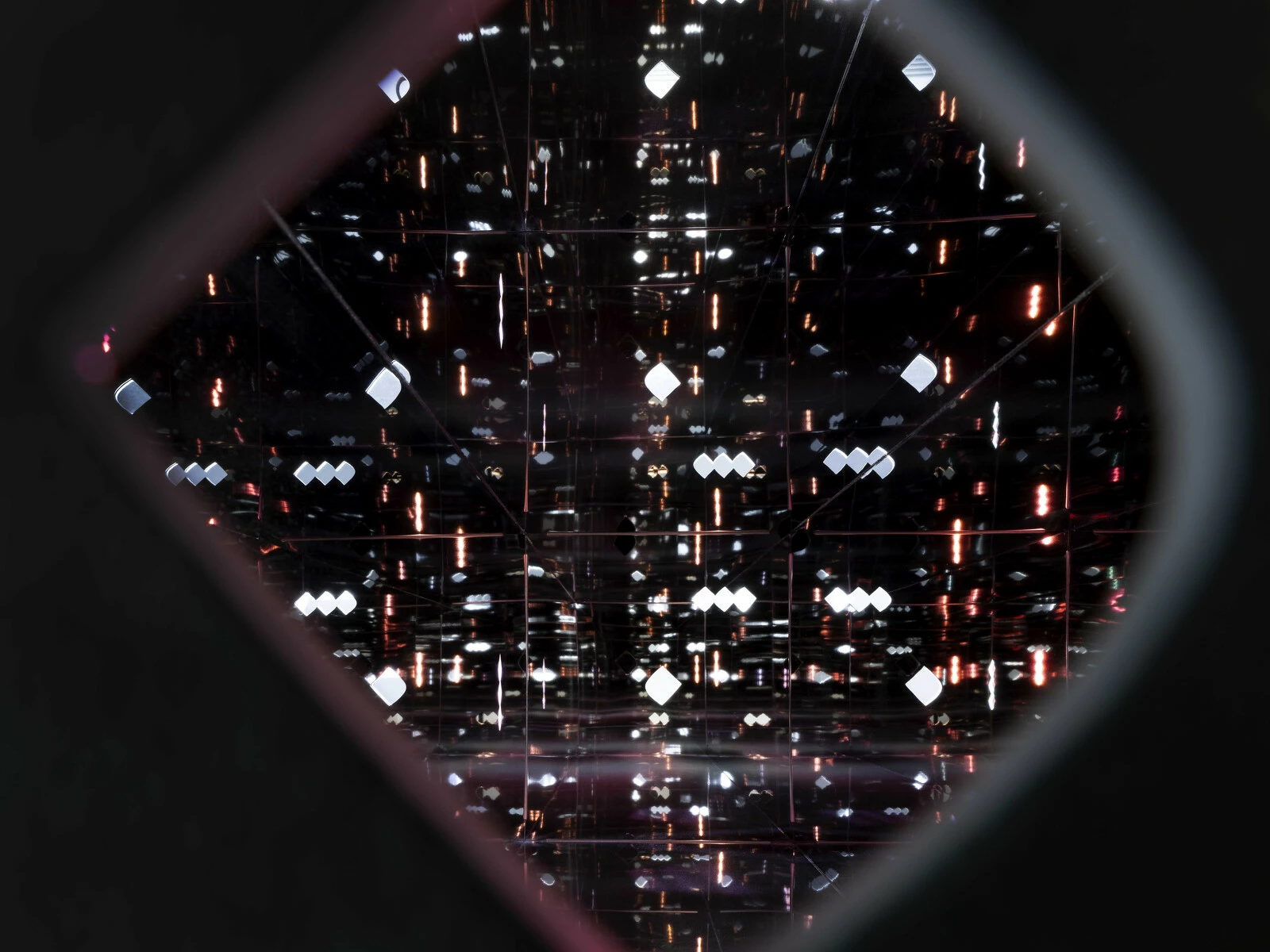

Before visitors enter the exhibition, they are welcomed by a series of cut-outs in the shape of noghte(s) made in the external gallery wall, part of a piece called Quadrilateral view (2023). When visitors peer through this aperture on either side of the wall, they encounter a mirrored prism installed within. This prism houses countless reflections of the noghte motif, a nod to the concept of infinite possibility in Islamic geometric patterns. Here, Taghavi carefully manipulates materials and light to create something that transcends physical constraints to become infinite and, perhaps, magical. Taghavi’s prisms, including this one, are mobile vessels that manifest in different ways each time they are installed in a new space, revealing many versions of infinity.

A second prism, Pentagonal view (2023), is revealed upon entering the exhibition. It is housed within the wall of another work—a site-specific architectural intervention titled Hashti (2023). Designed by Taghavi, the walls of this space form a 12-sided shape, or dodecagon, modeled after a geometric space in Persian architecture. Known as the hashti, this liminal area connects the gate or entrance of a building and the doorway leading to the interior. Traditionally, the hashti serves as a mediator between outside and inside—a place to pause and acknowledge transition.

As visitors progress from Hashti into the second gallery, Taghavi decisively pulls back the curtain to offer a glimpse into the innerworkings of her process. She reveals the reality behind her prisms by displaying a third prism, Unfolded Hexagon (2023), unwrapped, or disassembled, on the floor of the gallery, and a fourth, Triangular View (2023), installed as a free-standing sculpture with which visitors can interact. Here, Taghavi affirms the magic inherent to these works—and then purposefully negates it by revealing the illusion.

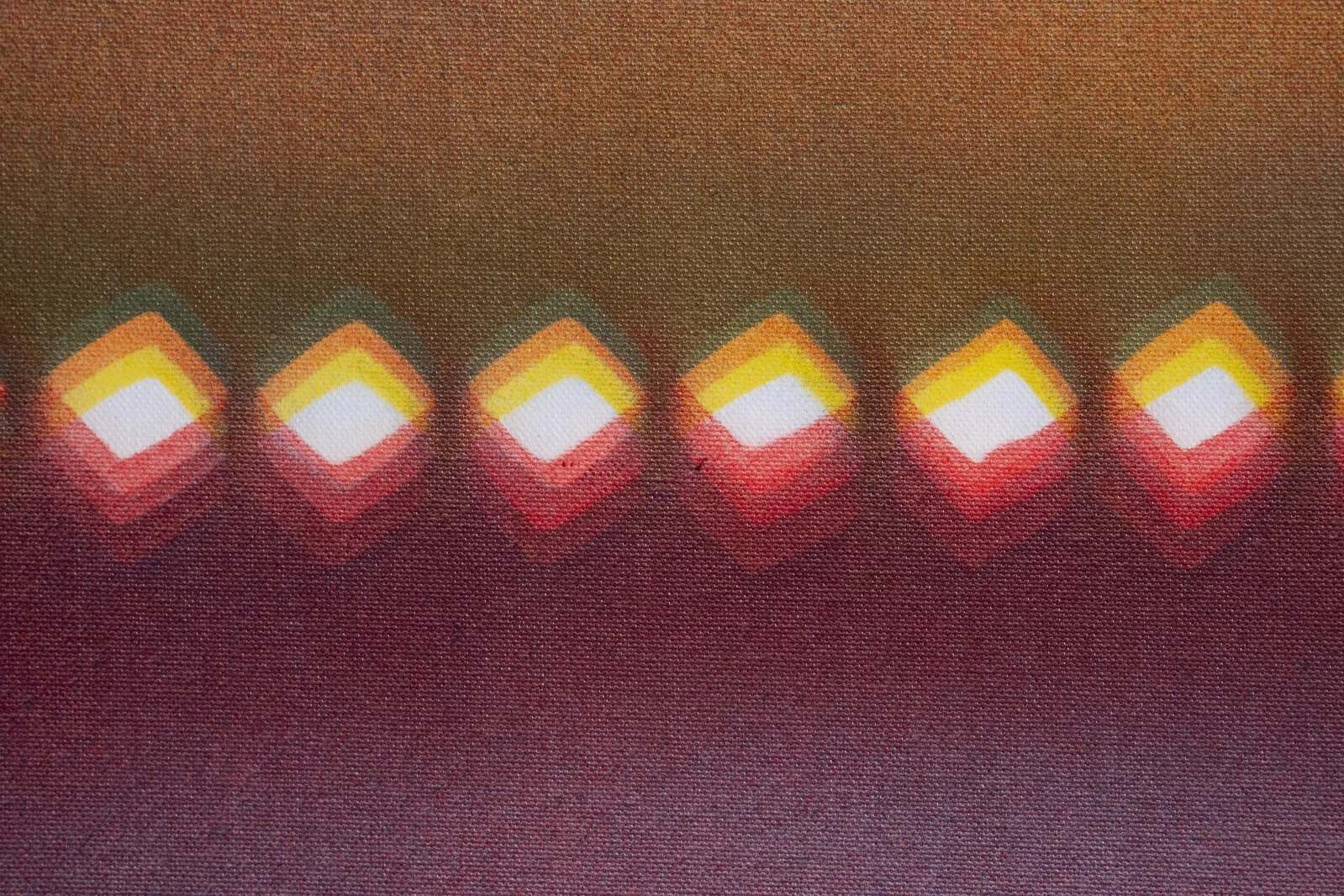

Nearby, six of Taghavi’s paintings from the series Horizon are set against a dark green background. These large-scale, airbrushed works evoke a fragmented horizon, suggested by the familiar noghte, which appears in clusters of three, five, or ten. Taghavi describes the horizon as “the place where the earth meets the sky, an imagined line that our eyes make up, a distance we cannot reach . . . I think there’s something incredibly powerful about that mode of imagination.”[3] Nodding to the noghte’s origins as a form of measurement, these works invite the viewer to consider that uncertain line, and the assumptions their eyes make about its distance.

By pushing back on the viewer’s perception of space, Taghavi’s paintings engage with a longstanding artistic tradition prevalent in Persian miniature painting in which artists flatten the horizon line, thus obscuring the viewer’s depth perception. Historically, Western works of art were governed by the laws of perspective. Three-dimensional space was projected onto a two-dimensional canvas. Artists painted toward a vanishing point to mimic how distance is perceived in real life. While artists in the West concerned themselves with painting reality, Persian miniaturists “presented things as they should be, not necessarily as they are.”[4] Objects in the background were not depicted as being smaller as they moved further from the foreground. Instead, they were placed at the top of the painting, where they remained proportionally the same size as those at the bottom of the painting. The miniaturists’ vertical approach invites the viewer to “perceive space in a more active way,” where “individuals become part of the whole picture, the whole surrounding space.”[5]

As an Iranian artist living in the diaspora for more than 23 years, Taghavi’s practice can also be considered through the postcolonial writings of Homi K. Bhabha. In his book The Location of Culture (1994), Bhabha writes, “The ‘beyond’ is neither a new horizon, nor a leaving behind of the past . . . we find ourselves in the moment of transit where space and time cross to produce complex figures of difference and identity, past and present, inside and outside, inclusion and exclusion.”[6]

In Taghavi’s work, these crossings are both physical and imaginary. To live in the diaspora is to live outside of context. Similar to Taghavi herself, the noghte has been taken out of its literary framework. In the Horizon paintings, the noghte is fragmented, unable to complete the horizon line. It floats in isolation from the letters it ordinarily adorns, allowed only to hold its basic form. In other works, such as within the expanse of the artist’s mirrored prisms, the noghte is liberated, bending and morphing in the light, adjoined to nothing. Again and again in Taghavi’s work, we are asked to use our imaginations. To connect the dots, to dream of the horizon. To face incompleteness, and to exist in the in-between.

In his writing, Bhabha also insists that migrants are active, and not passive, subjects in the transmission of culture—from homeland to host land and back again.[7] This is a useful framework for situating contemporary artists such as Taghavi within a broader, generational shift in Iranian art history identified by scholar Hamid Keshmirshekan. In his essay The Question of Identity vis-à-vis Exoticism in Contemporary Iranian Art (2010), Keshmirshekan describes how many artists working in the 1960s—such as those associated with the Saqqakhaneh movement—incorporated preexisting decorative and traditional motifs related to the ancient, religious, folk, and calligraphic arts in their practice. Their work was identified as especially “Iranian.” While these Saqqakhaneh artists were keenly interested in drawing from Iranian popular culture, those who followed them opposed the use of cultural codes and stereotypes that risked carrying a sense of exoticism into the West. Consequently, over the past two decades a younger generation of artists presented work that featured ironic, kitschy, and sometimes humorous approaches. Through this deconstruction, these artists challenge exoticism, posit a multiplicity of identities, and defy the notion of a singular, unified identity expressed by the previous generation. Yet despite their differences, when compared these two groups share a core concern of collective belonging: where the older generation focuses on national artistic identity by celebrating the traditional, the newer generation challenges the concept of fixed identity through critical and subversive expressions.[8]

Visitors to Taghavi’s exhibition encounter this dynamic in a work titled Heechi (2023). The sculpture is inspired by the artist Parviz Tanavoli, nicknamed the “father of Iranian sculpture,”[9] who pointedly uses source material rooted in Iranian culture and translates it into modernist and abstract forms—such as in his Heech series, which he began in 1965. Referencing both Persian literature and calligraphy, his series uses characters to spell out the Farsi word heech, which translates to “nothing,” a concept used in the Sufi spiritualism of renowned 13th-century poet Mawlana Jalal al-Din Muḥammad Rumi, whose verses explore the concept of nonbeing—not as the termination of being, but as the path to fulfillment and the wholeness of being.

Though Taghavi’s sculpture Heechi is inspired by Tanavoli’s Heech series, she has added a single letter to the word, transforming “heech” into “heechi.” In contrast to “heech,” which represents a nothingness that leads to wholeness and fulfillment, the word “heechi” can be translated into a nothingness that represents emptiness and void. In Taghavi’s words, “that level of divine is removed from it. It’s very much looking down on earth and the everyday . . . [heechi is] the nothing as it appears in life’s disappointments or despair.”[10] If Tanavoli’s Heech series affirms a spiritual tradition, Taghavi uses linguistic slippage and transliteration to question, subvert, and reveal the Heechi. She is not only defying tradition—she is defying an older generation’s fidelity to that tradition, as well as challenging the notion of a fixed identity. “The way of heechi is recognizing my distance to the context where it comes from, to what actually constitutes this idea of perfection and what is profound and spiritual,” she says. “So, I am removing that as a way of recognizing how impossible it may be to hold on to those ideas and thoughts, from where I stand.”[11]

The final work in the exhibition is a small calligraphed text. It is the only work that contains multiple words. To create it, Taghavi commissioned calligrapher Parisa Shafiei to etch an excerpt from a poem [Ghazal #551] by the 13th-century poet Saadi Shīrāzī in a style of calligraphy that is purposefully devoid of noghte(s). Without them, the reader needs to slow down to access the meaning of the text. The poem reflects on the state of longing and the persistence of a beloved’s memory. Elsewhere in the exhibition the noghte refracts through a prism or floats in a painting, separated from the context of letters. Yet here, in Taghavi’s final work, readers experience the inverse: the pure context of letterforms devoid of the noghte(s) that provide their discerning sounds.

In the poem and across her practice, Taghavi uses removal and abstraction to address distance in several forms: spatial, generational, and diasporic. “I am not practicing calligraphy. I am not practicing this perfection,” she says. “I am far away from the context that it comes from. I do have this thread to this language, to this culture, but it’s really hard to preserve it . . . with the distance that I have from it [and] with the time that we are living in.”[12] In Nothing Is, Taghavi asks you to become an active participant in experiencing this distance. If you choose to partake in her choreography of bending, peering, imagining, and connecting, you get to participate in the act of transforming from heech to heechi—materially, conceptually, and experientially.

Español

Maryam Taghavi y la coreografía de la nada

BANA KATTAN

En persa y árabe, el noghte es el signo diacrítico más esencial. El número de noghte(s) encima o debajo de una letra en particular indica su sonido: por ejemplo, la misma letra puede convertirse en b, y, p, n, t o th, dependiendo de la disposición del noghte. Traducido libremente al español como “punto”, en caligrafía este signo diacrítico se graba con la punta inclinada de una pluma de bambú, creando una forma similar a un diamante. A principios del siglo X, en la actual Bagdad, un visir de los califas abasíes llamado Ibn Muqla desarrolló un sistema para determinar el tamaño de las letras en un alfabeto basado en el noghte. Muqla calculó la altura de la primera letra del alfabeto árabe, el alif, siguiendo la altura de una serie de noghte(s); luego determinó el tamaño de las demás letras en relación con el alif [1]. Desde que Muqla inventó la “escritura proporcional”, el noghte se utiliza como unidad de medida para todas las relaciones espaciales de una composición caligráfica (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Litografía del siglo XIX de una escritura en estilo Naskh, una de las primeras formas de caligrafía islámica. Cortesía de Borna Izadpanah.

Según la artista Maryam Taghavi (n. Teherán, Irán; vive en Chicago, IL), para la cultura literaria el noghte es “lo que la semilla es para un árbol. Es imposible pensar que esta pequeña unidad contenga el plano de un árbol entero, pero ahí está. Y pienso de la misma manera sobre el punto o ‘noghte’; es como la entrada a todo un mundo”.[2] En la exposición de Taghavi en el MCA, Obras de Chicago: Maryam Taghavi, el noghte emerge como un aspecto central que influye tanto en la construcción del significado como en la forma en que se percibe la distancia. En la instalación, titulada paradójicamente Nada es, Taghavi utiliza cuidadosamente elementos de una cultura visual con la que creció, junto con tradiciones extraídas de la caligrafía islámica, las pinturas en miniatura y arquitectura persas. El tratamiento que Taghavi da a estas tradiciones es reverencial, aunque también es sutilmente irreverente. Con ironía, abstracción y transliteración, su obra se mueve entre lo trascendental y lo transgresivo: algo que se refleja en el espacio de la exposición.

Antes de entrar a la exposición, una serie de recortes en forma de noghte(s), en la pared externa de la galería, que forman parte de la pieza Vista cuadrilátera (2023), dan la bienvenida. Si los visitantes miran a través de esta abertura, en ambos lados de la pared, se encontrarán con un prisma espejado. Este alberga innumerables reflejos del noghte, una alusión al concepto de posibilidad infinita de los patrones geométricos islámicos. Aquí, Taghavi manipula cuidadosamente los materiales y la luz para crear algo que trasciende las limitaciones físicas para volverse infinito y, tal vez, mágico. Los prismas de Taghavi, como este, son recipientes móviles que se manifiestan de diferentes maneras, cada vez que se instalan en un nuevo espacio, y revelando muchas versiones del infinito.

Un segundo prisma, Vista pentagonal (2023), está en la intervención arquitectónica Hashti (2023). Las paredes de este espacio forman un dodecágono (doce lados). Es una construcción que ha sido modelada siguiendo un espacio geométrica liminal de la arquitectura persa conocida como hashti, o el área entre la entrada de un edificio y la puerta que conduce al interior. Tradicionalmente, el hashti sirve como mediador entre el exterior y el interior: una pausa para resaltar una transición.

Camino hacia la segunda galería, Taghavi descorre la cortina para ofrecer un vistazo de su proceso interno. Revela la realidad detrás de sus prismas con un tercero, Hexágono desplegado (2023), abierto o desarmado en el piso de la galería, y un cuarto prisma, Vista triangular (2023), instalado como una escultura independiente con la que los visitantes pueden interactuar. Aquí, Taghavi confirma la magia inherente a estas obras y luego la niega deliberadamente al revelar la ilusión.

Cerca de estos, seis de las pinturas de Taghavi de la serie Horizonte están sobre un fondo verde oscuro. Estas obras a gran escala y retocadas con aerógrafo evocan un horizonte fragmentado, sugerido por el ya familiar noghte, que aparece en grupos de tres, cinco o diez. Taghavi describe el horizonte como “el lugar donde la tierra se encuentra con el cielo, una línea imaginaria que nuestros ojos crean, una distancia que no podemos alcanzar… Creo que hay algo increíblemente poderoso sobre ese modo de imaginación”.[3] Haciendo alusión al origen del noghte como forma de medición, estas obras invitan al espectador a pensar en esa línea incierta y en las suposiciones que sus ojos hacen de su distancia.

Al rechazar las percepciones que las audiencias pueden tener sobre el tiempo y el espacio, las pinturas de Taghavi se insertan en una larga tradición artística prevalente en la pintura en miniatura persa, donde los artistas aplanan la línea del horizonte, ocultando así la percepción de profundidad del espectador. Históricamente, las obras de arte occidentales se regían por las leyes de la perspectiva. Un espacio tridimensional se proyectaba sobre un lienzo bidimensional. Los artistas pintaban hacia un punto evanescente para imitar la forma en que se percibe la distancia en la vida real. Mientras los artistas occidentales buscaban retratar la realidad, los miniaturistas persas “presentaban las cosas como deberían ser, no necesariamente como son”.[4] Los objetos en el fondo no se representaban más pequeños a medida que se alejaban del primer plano, sino que se colocaban en la parte superior de la pintura y permanecían proporcionalmente del mismo tamaño que los de la parte inferior. El enfoque vertical de los miniaturistas invita al espectador a “percibir el espacio de una manera más activa”, donde “los individuos son parte de la imagen completa, de todo el espacio circundante”.[5]

Como artista iraní que vive en la diáspora hace más de veintitrés años, la práctica de Taghavi también puede verse a través de los escritos poscoloniales de Homi K. Bhabha. En su libro La localización de la cultura (1994), Bhabha escribe: “El ‘más allá’ no es un nuevo horizonte ni un dejar atrás el pasado… es un momento en que el espacio y el tiempo se cruzan para producir figuras complejas de diferencia e identidad, pasado y presente, dentro y fuera, inclusión y exclusión”.[6]

En la obra de Taghavi, estos cruces son tanto físicos como imaginarios. Vivir en la diáspora es vivir fuera de contexto. Al igual que la propia Taghavi, el noghte ha sido sacado de su marco de referencia literario. En las pinturas de Horizonte, este ha sido fragmentado, sin poder completar la línea del horizonte. Es un signo que flota aislado de las letras que normalmente adorna y que solo mantiene su forma básica. En otras obras, como en los prismas espejados, el noghte se libera, se dobla y se transforma en una luz, como si se uniera a la nada. Una y otra vez, en la obra de Taghavi, se nos pide usar nuestra imaginación: conectar los puntos, soñar con el horizonte, enfrentar lo incompleto y existir en un espacio medio.

En sus escritos, Bhabha también insiste en que los inmigrantes son sujetos activos, y no pasivos, en la transmisión de la cultura, desde la patria a la tierra anfitriona y viceversa.[7] Este es un marco de referencia útil para situar a artistas contemporáneos como Taghavi dentro de un cambio generacional más amplio en la historia del arte iraní, según el académico Hamid Keshmirshekan. En su ensayo La cuestión de la identidad respecto al exotismo en el arte iraní contemporáneo (2010), Keshmirshekan describe cómo muchos artistas que trabajaron en los sesenta —como los asociados con el movimiento Saqqakhaneh— incorporaron en su práctica elementos decorativos y tradicionales relacionados con las artes antiguas, religiosas, folklóricas y caligráficas. Sus obras eran identificadas como “iraníes” en esencia. Si bien los artistas de Saqqakhaneh buscaban inspiración en la cultura popular iraní, los que siguieron se opusieron al uso de códigos culturales y estereotipos que pudieran ser “exóticos” en Occidente. Como consecuencia, durante las últimas dos décadas una generación más joven de artistas presentó obras con enfoques irónicos, cursis y, a veces, humorísticos. Con esta deconstrucción, estos artistas desafiaron el exotismo y plantearon una multiplicidad de identidades en contra de la noción de esa singular y unificada identidad de la generación anterior. A pesar de las diferencias, estos dos grupos, cuando se comparan, comparten una preocupación fundamental por la pertenencia colectiva: mientras que la generación anterior se centra en la identidad artística nacional que celebra lo tradicional, la generación más nueva desafía crítica y subversivamente el concepto de identidad fija.[8]

En la exposición de Taghavi se ve esta dinámica en la obra titulada Heechi (2023). La escultura está inspirada en el artista Parviz Tanavoli, apodado como el “padre de la escultura iraní”[9], quien intencionalmente utiliza material arraigado en la cultura iraní y lo lleva a formas modernistas y abstractas, como en su serie Heech, comenzada en 1965. Haciendo referencia a la literatura persa y la caligrafía, esta serie usa caracteres para deletrear la palabra farsi heech (traducida como “nada”), un concepto del espiritualismo sufí del renombrado poeta del siglo XIII Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi, cuyos versos exploran el concepto del “no ser”, no como la terminación del ser, sino como el camino hacia la integridad y plenitud del ser.

Aunque la escultura Heechi se inspira en el Heech de Tanavoli, Taghavi le ha agregado una sola letra a la palabra, transformando el “heech” en “heechi”. En contraste con heech, que representa una nada que conduce a la integridad y la plenitud, la palabra heechi se traduce como una nada que representa la futilidad y el vacío. En palabras de Taghavi, “se le ha eliminado lo divino. Ahora contempla hacia abajo, hacia la tierra y lo cotidiano… [el heechi] como una nada que aparece en las decepciones o angustias de la vida”.[10] Si la serie Heech de Tanavoli confirma una tradición espiritual, Taghavi utiliza el deslizamiento lingüístico y la transliteración para cuestionar, subvertir y revelar el Heechi. Así, no solo desafía la tradición, sino también la fidelidad de una generación anterior a esa tradición, y la noción de una identidad fija. “El heechi reconoce mi distancia del contexto de donde proviene, de lo que constituye esa idea de la perfección y lo que es profundo y espiritual”, dice la artista. “Lo estoy eliminando como una forma de reconocer cuán imposible puede ser aferrarse a esas ideas y pensamientos”.[11]

La exposición cierra con un pequeño poema en caligrafía. Es la única obra que contiene varias palabras. Para crearlo, Taghavi le pidió a la calígrafa Parisa Shafiei que hiciera un grabado de un fragmento de un poema [Ghazal #551], del poeta del siglo XIII Saadi Shīrāzī, con una caligrafía que fuera deliberadamente despojada de noghte(s). Sin estas marcas, el lector necesita disminuir la velocidad para acceder al significado del texto. El poema reflexiona sobre la nostalgia y el persistente recuerdo de un ser querido. En las otras partes de la exposición, Taghavi utiliza el noghte como una forma que, al refractarse a través de un prisma o flotar en una pintura, se ha divorciado del contexto de las letras. Sin embargo, aquí, en el último trabajo de Taghavi, los lectores experimentan lo inverso: el contexto puro de letras sin noghte(s) que proporcionan sonidos más finos.

Tanto en el poema como en sus obras, Taghavi recurre a la remoción y abstracción para abordar la distancia de varias formas: espaciales, generacionales y diaspóricas. “No estoy haciendo caligrafía. No me interesa esa perfección”, dice. “Estoy muy alejada del contexto del que viene. Sí tengo una conexión con este lenguaje, con esta cultura, pero es muy difícil preservar esto . . . debido a la distancia y el tiempo en que vivimos”.[12] En Nada es, Taghavi invita a los espectadores a experimentar esta distancia. Si decides formar parte de su coreografía, que incluye inclinarse, mirar, imaginar y conectar, podrás participar, de manera material, conceptual y experiencial, en el acto de transformación de un heech en un heechi.

فارسی

بانه قطان

برگردان باوند بهپور

در زبان فارسی و عربی، نقطه مهمترین علامت نگارشی است. تعداد نقطههایی که کاتب بالا یا پایین حروف میگذارد صدای آنها را تعیین میکند: برای مثال، یک شکل واحد، بسته به نقطههایش ممکن است «بـ»، «یـ»، «پـ»، «نـ»، «تـ»، یا «ثـ» خوانده شود. «نقطه» که آن را در انگلیسی با قدری مسامحه به dot یا point ترجمه میکنند در خوشنویسی به لکهای لوزیشکل گفته میشود که از حرکت نیش مورب قلم نی پدید میآید. در اواخر قرن سوم هجری در بغداد، ابن مقله، وزیر دربار عباسی، شیوهای برای سنجش حروف الفباء بر پایة نقطه ابداع کرد. او ارتفاع اولین حرف الفباء یعنی الف را با نقطه سنجید و سپس طول سایر حروف را با الف مقایسه کرد. از زمان «خط تناسبی» ابن مقله به بعد، نقطه به عنوان واحد سنجش تناسبات فضایی ترکیببندی در خوشنویسی به کار گرفته شده است. (شکل ۱)

برای مریم تقوی (متولد تهران، ساکن شیکاگو) نسبت نقطه به کلام مانند نسبت دانه به درخت است: «سخت بتوان تصور کرد که این جزء کوچک، کل ساختار درخت را در خود حمل میکند اما واقعاً همینطور است. من یک چنین تصوری از «نقطه» دارم: دری است به جهانی دیگر.» در نمایشگاه انفرادی تقوی در MCA با نام آثار شیکاگو: مریم تقوی، نقطه، نقشمایة اصلی است که هم بر ایجاد معنا و هم بر تلقی فرد از فاصله اثر دارد. در چیدمانی با نامِ متناقضِ «هستی هیچ» تقوی عناصری را از فرهنگی بصری که در آن بار آمده مانند سنتهای خوشنویسی اسلامی و نقاشی و معماری ایرانی به کار میگیرد. برخورد تقوی با این سنتها محترمانه و در عین حال رندانه است: بهکارگیری کنایه و انتزاع و وانویسی باعث میشود آثارش میان امر متعالی و هنجارشکن نوسان کنند: رفتوآمدی که در فضای نمایشگاه هم منعکس شده است.

بینندگان پیش از ورود به نمایشگاه با تعدادی نقطههای دوربریشده بر دیوار خارجی نمایشگاه مواجه میشوند که بخشی از اثری است به نام منظر چهارضعلی (۱۴۰۲). هنگامی که از هر سمت دیوار به درون این منفذ بنگرند منشوری آینهای میبینند که در دیوار تعبیه شده. این منشور بازتابهای بیشمار نقشمایة «نقطه» را به نمایش میگذارد، اشارهای به امکانات بیپایان نقوش هندسی اسلامی. در اینجا تقوی به ظرافت در مصالح و نور دست میبرد تا چیزی بیافریند که از مرزهای فیزیکی فراتر میرود و کیفیتی نامتناهی و سحرآمیز مییابد. منشورهای تقوی محملهای متحرکند که هر بار که در فضایی جدید نصب میشوند به شیوهای دیگر روی مینمایند و شکلهایی بسیار از نامتناهی را ظاهر میسازند.

منشوری دیگر به نام منظر پنجضلعی (۱۴۰۲) به هنگام ورود به نمایشگاه به چشم میآید و در دل یک مداخلة معمارانه به نام هشتی (۱۴۰۲) قرار دارد. دیوارهای این بخش، فضایی دوازدهضلعی میسازد. این سازه به فضایی آستانهای و هندسی به نام «هشتی» در معماری ایران شباهت دارد که حد فاصل ورودی ساختمان و راهروی منتهای به فضاهای داخلی بوده است. هشتی فضایی مابین درون و بیرون است: مکثی برای تشخیص گذار.

زمانی که بیننده از هشتی به گالری دوم پا میگذارد، تقوی پرده را قاطعانه کنار میزند تا سازوکار فرایندش را آشکار کند. او واقعیت پشت منشورهایش را با نمایش منشوری سوم به نام ششضلعیِ گشاده (۱۴۰۲) که بر کف گالری از هم باز شده و همچنین منشوری چهارم به نام منظر سهضلعی (۱۴۰۲) که مانند مجسمهای مجزا و تعاملی است آشکار میکند. در اینجا تقوی نخست جنبة سحرآمیز این آثار را به رخ میکشد و سپس با آشکار کردن سویة وهمآمیزش، همین سحر را باطل میکند.

قدری آنطرفتر پنج نقاشی تقوی از مجموعة افق بر پسزمینة سبز تیره قرار گرفتهاند. این آثار بزرگ و رنگپاشیشده، خط افق منقطعی را تداعی میکنند که با دستههای سه و پنج و دهتایی نقاط به تصویر کشیده شده. تقوی افق را چنین توصیف میکند: «جایی که زمین به آسمان میرسد؛ خطی فرضی که چشممان میسازد؛ جایی که نمیتوانیم به آن برسیم… من فکر میکنم چنین خیالی بسیار قدرتمند است.» با ارجاع به سابقة «نقطه» به مثابه واحد سنجش، این آثار از بیننده میخواهند که آن خط نامعین را در خیال خود مجسم سازند و تصوری را که چشمشان از فاصله میسازد در نظر بگیرند.

نقاشیهای تقوی پیشفرضهای بیننده را در مورد ادراک فضا برهم میزنند و سروقت سنت دیرین نگارگری ایرانی میروند که هنرمند در آن، خط افق را تسطیح و درک بیننده از عمق را مبهم میسازد. پرسپکیتو در طول تاریخ بر هنر غرب استیلا داشته. فضای سهبعدی بر بومی دوبعدی انعکاس مییافته. هنرمندان به سمت نقطة گریز نقاشی میکردند تا ادراک واقعی فاصله را تقلید کنند. برخلاف هنرمندان غربی که دغدغة نقاشی کردن از واقعیت داشتند نگارگران ایرانی «چیزها را چنانکه باید نشان میدادند نه آنچنانکه هست.» اشیاء دورتر، کوچکتر نمایش داده نمیشدند بلکه با همان تناسباتی در بالای نقاشی قرار میگرفتند که اشیاء پایین صفحه داشتند. رویکرد عمودی نگارگران بینندگان را دعوت میکرد که «فضا را به شیوهای پویاتر ببینند» به گونهای که «آدمها بخشی از کل تصویر و فضای پیرامونی میشوند.»

آثار تقوی را به مثابه هنرمندی ایرانی که بیش از بیستوسه سال در غربت زندگی کرده میتوان از منظر نوشتههای پسااستعماری هومی ک. بابا نیز بررسی کرد. بابا در کتاب مکان فرهنگ (۱۳۷۲) مینویسد: «فضای «ماورا» نه افقی جدید است و نه ترک گذشته… ما خودمان را در لحظهای مییابیم که در تقاطع فضا و زمان، اشکال پیچیدهای از تفاوت و هویت، گذشته و اکنون، بیرون و درون و پذیرش و طرد آفریده میشود.»

در آثار تقوی این تقاطع هم واقعی و هم خیالی است. زیستن در غربت، زیستن در پسزمینهای نامرتبط است. «نقطه» مانند خودِ هنرمند از چارچوبش خارج میشود. در نقاشیهای با عنوان افق، نقطه تکهتکه شده و قادر نیست خط افق را کامل کند. جداافتاده از حروفی که تزئینگرشان بوده، نقطه معلق میشود و صرفاً اجازه مییابد که شکل اصلیش را حفظ کند. در آثار دیگر، نظیر منشورهای آینهای، نقطه آزاد میشود و در روشنایی تاب برمیدارد و تغییر شکل میدهد و به چیزی نمیچسبد. در آثار تقوی مکرر در مکرر از ما خواسته میشود که خیالمان را به کار بگیریم و نقاط را به هم وصل کنیم و افق را تصور کنیم؛ با ناتمامی مواجه شویم و در فضایی بینابینی باشیم.

بابا در نوشتههایش همچنین اصرار دارد که مهاجران فعالند نه منفعل، و عاملان انتقال فرهنگند: از موطنشان به سرزمین میزبان و برعکس. این چارچوبی مفید برای مکانیابی هنرمندان معاصری چون تقوی است در سیر گذار نسلی در تاریخ هنر ایران؛ سیری که حمید کشمیرشکن بهخوبی تبیین کرده است. در مقالة «مسئله هویت در مواجهه با اگزوتیسم در هنر معاصر ایران» (۱۳۸۹) کشمیرشکن توضیح میدهد چه گونه بسیاری از هنرمندان دهة چهل شمسی (از جمله سقاخانهایها) نقشمایههای سنتی و تزئینی هنرهای باستانی، مذهبی، فولکلور و خوشنویسی را در آثارشان آوردند؛ آثاری که مشخصاً «ایرانی» قلمداد شدهاند. هرچند سقاخانهایها به بهرهگیری از فرهنگ عامیانه ایران علاقهمند بودند اخلافشان با کاربرد نشانههای فرهنگی و کلیشههایی که امکان داشت حس اگزوتیسم به غرب بدهد مخالفت کردند. در نتیجه در عرض دو دهه، نسل جوان هنرمندان آثاری آفریدند که رویکردی کنایی، کیچ و گاهی طنزآمیز داشت. از طریق یک چنین واسازیی، این هنرمندان، اگزوتیسم را به چالش کشیدند و هویتهایی متکثر را پیش رو نهادند و تصور هویت منسجم و واحد را که نسل قبل مد نظر داشت انکار کردند. به رغم این تفاوتها، حس تعلق جمعی دغدغهای مشترک برای هر دو گروه بود: نسل قبل با بزرگداشت سنت بر هویت هنری ملی تأکید داشت و نسل جدید ایدة هویت صلب را با رویکردی انتقادی و شورشی به چالش میکشید.

بازدیدکنندگان نمایشگاه تقوی با این ماجرا در اثری به نام هیچی (۱۴۰۲) مواجه میشوند. این مجسمه ملهم از کارهای پرویز تناولی است؛ کسی که عنوان «پدر مجسمهسازی ایرانی» را یدک میکشد و رندانه مصالح قدیمی فرهنگ ایرانی را به کار میگیرد و آنها را (برای مثال در مجموعة «هیچ» خود که در سال ۱۳۴۴ آغاز کرد) به فرمهای مدرن و انتزاعی ترجمه میکند. این مجموعه با ارجاع به خوشنویسی و ادبیات ایران، از نوشتار بهره میگیرد تا واژة فارسی «هیچ» را به تصویر بکشد، معنایی که در عرفان شاعر معروف قرن هفتم هجری مولانا جلالالدین محمد بلخی به کار رفته است؛ او در اشعارش مفهوم «عدم» را نه در معنای پایان وجود، بلکه به معنی مسیری برای تحقق و کمال آن میکاود.

هر چند مجسمة «هیچی» تقوی از «هیچ»های تناولی الهام گرفته اما تقوی یک حرف به این کلمه اضافه کرده و «هیچ» را بدل به «هیچی» ساخته است. برخلاف «هیچ» که بیانگر عدمی است که به کمال و تحقق میرسد کلمة «هیچی» را میتوان به نبودی ترجمه کرد که پوچی و خلأ را تداعی میکند. به بیان تقوی: «جنبة مقدسش حذف شده و زمینیتر و روزمرهتر شده… هیچی در معنای سرخوردگی و ناامیدیی که در زندگی پیش میآید.» اگر «هیچ»های تناولی بر سنتی معنوی صحه میگذارند تقوی لغزش زبانی را به کار میگیرد تا «هیچی» را به پرسش بگیرد و وارونه و ظاهر سازد. او عنادی با سنت ندارد بلکه با اتکای نسل قبل به سنت مخالف است و مفهوم هویت ثابت را به چالش میکشد. « هیچی فاصلة مرا با پسزمینهای که از آن میآید و آنچه سازندة ایدة کمال و امر متعالی و قدسی است معتبر میداند. در نتیجه آن را حذف میکنم تا نشان بدهم از دید من، چه ناممکن است بتوان به این ایدهها و عقاید وفادار ماند.»

آخرین اثر نمایشگاه، یک شعر کوچک خوشنویسیشده است. این تنها اثر نمایشگاه است که از چند واژه تشکیل شده. برای خلق آن تقوی شعری از سعدی شاعر قرن هفتم هجری را به پریسا شفیعی خوشنویس سفارش داد که به شیوهای بنویسد که در آن ترکیبها عمداً فاقد نقطهاند. بدون این نقاط خواننده ناگزیر است شعر را کندتر بخواند تا بفهمد. شعر در باب اشتیاق به معشوق و خاطرة خیال اوست. در بخشهای دیگر نمایشگاه، تقوی نقطه را به مثابه فرمی به کار میگیرد که در منشور میشکند یا در نقاشی معلق است و از پس زمینة حروف خارج میشود. اما در اینجا، در این آخرین اثر، خوانندگان عکس این ماجرا را تجربه میکنند: پسزمینة خالص حروف بینقطه که صدا تولید میکنند.

در این شعر و در کل آثارش، تقوی حذف و انتزاع را به کار میگیرد تا به فاصله در اشکال متفاوت فضایی، نسلی و مرتبط با دوری از وطن بپردازد: «من خطاط نیستم. مشق کمال نمیکنم. خیلی از این زمینه دورم. اتصالی با این زبان و فرهنگ دارم اما با فاصلهای که از آن گرفتهام و با وجود این روزگاری که از سر میگذرانیم بسیار دشوار میتوانم نگهش دارم.» در «هستی هیچ» تقوی از شما میخواهد که مشارکتی فعال در تجربه کردن این فاصله داشته باشید. اگر بخواهید در رقصنگاری این پیچش و نگرش و خیال و اتصال شریک شوید امکان این را خواهید یافت که به صورت ذهنی، عملی و واقعی هیچ را به هیچی بدل سازید.

Footnotes

FOOTNOTES

1 Jonathan M. Bloom, Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), p. 108.

2 Maryam Taghavi, interview with Bana Kattan, September 27, 2023.

3 Kerry Cardoza, “Spell Casting,” Chicago Reader, October 16, 2023.

4 Sheila Canby, Persian Painting (Northampton: Interlink Publishing, 1993), p. 7, quoted in Carmen Pérez González, A Comparative Visual Analysis of Nineteenth-Century Iranian Portrait Photography and Persian Painting (PhD diss., University of Leiden, 2010), p 109.

5 Pérez González, p. 95.

6 Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (Oxfordshire: Routledge, 1994), pp. 227–28.

7 Bhabha, pp. 227–228.

8 Hamid Keshmirshekan, “The Question of Identity vis-à-vis Exoticism in Contemporary Iranian Art,” Iranian Studies Vol. 43, No. 4 (September 2010), pp. 489–512.

9 Venetia Porter, ed., Parviz Tanavoli, A Life in Art. (Tehran: Nazar Art Publications, 2022), pp. 5–10.

10 Taghavi and Kattan.

11 Taghavi and Kattan.

12 Taghavi and Kattan.

Funding

Lead support is provided by R.H. Defares and Zell Family Foundation.

Major support is provided by DIOR, Susie L. Karkomi and Marvin Leavitt, Robin Loewenberg Tebbe and Mark Tebbe, and Charlotte Cramer Wagner and Herbert S. Wagner III of the Wagner Foundation.

Generous support is provided by the Sandra and Jack Guthman Chicago Works Exhibition Fund.

This exhibition is supported by the Women Artists Initiative, a philanthropic commitment to further equity across gender lines and promote the work and ideas of women artists.