Living, Breathing History in Anne Collod’s Moving alter-natives

by Laura Paige Kyber

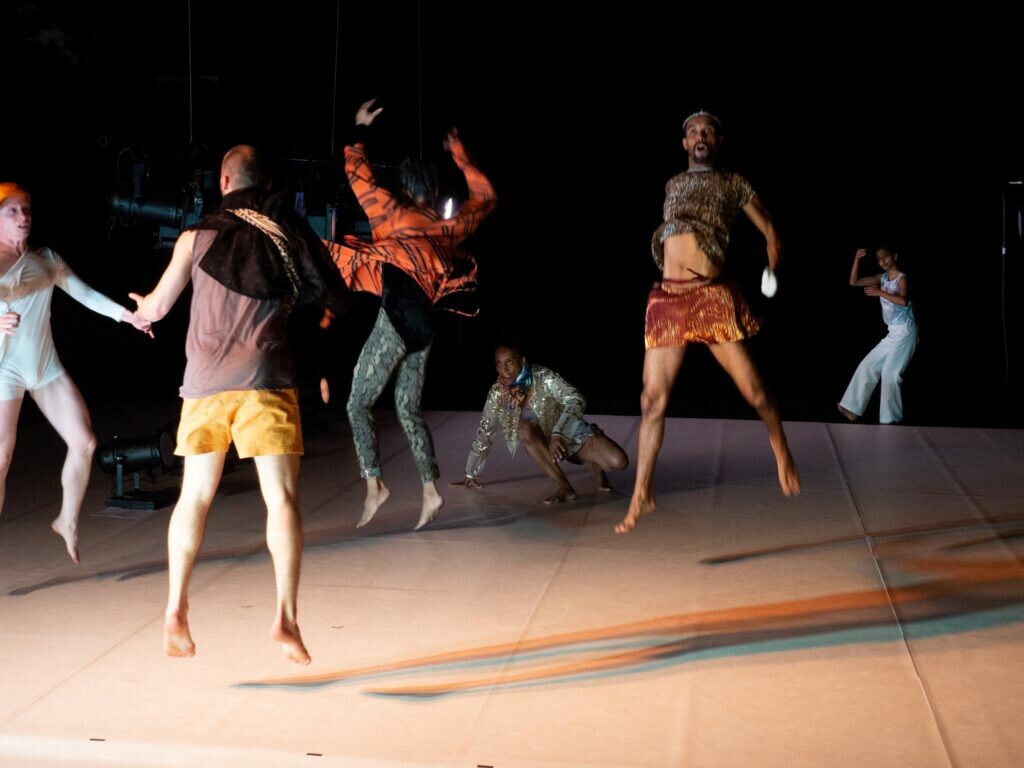

Anne Collod, Moving alter-natives, 2019. Photo: Jacques Hoepffner.

In February, the MCA’s 2025 On Stage series continues to explore its guiding concept of Lineages with choreographer Anne Collod’s Moving alter-natives. In this work, Collod asks what it means for the foundations of modern dance history in the United States to be influenced by the work of lauded dance icons Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. Known for incorporating South and East Asian, Egyptian, and Native American traditional styles in their choreography, St. Denis and Shawn are of particular interest to Collod, whose contemporary restagings explore, among other things, the fine line between cultural appropriation and celebration, especially as drawn through the pair’s work. Both professional and personal partners, St. Denis and Shawn are often regarded as the “founders” of modern dance in the US, having opened Denishawn as a school and company in 1914, and nurturing several leaders of the next generation of modern dance including Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Weidman. Despite their profound impact on the field of dance, many of today’s dance artists and scholars are concerned with the orientalist and appropriative nature found at the roots of their storied history.

At the core of Collod’s Moving alter-natives are six faithful restagings from the duo’s oeuvre, including St. Denis’s Incense (1906), two of her famed “Nautch solos” (1917–19), Shawn’s The Dome (1933), and excerpts from his Kinetic Molpai (1935). Interspersing these historic dances are newly choreographed sections and spoken interludes—some are recitations of archival texts, while others are personal reflections on what these dances mean to the performers. The work, for instance, opens with each performer entering the stage one by one, as if to introduce themselves. There are moments when the dancers find each other in unison, but then someone breaks off and begins a new dance of their own. Collod has titled this section “Memory Fragments / Kinesthetic Archives,” with each dancer drawing on their own influences and embodied choreographic memories. References range from traditional dance styles found in Brazil, India, and Israel, to popular television in the US and concert dances from Germany and France. From this opening moment, the audience begins to sense that with these historic restagings, the metaphoric fingerprints of the performers will be placed on the works.

Not unlike the work of Elisa Harkins, whose performance Wampum / ᎠᏕᎳ ᏗᎦᎫᏗ preceded Moving alter-natives in this year’s On Stage season, Collod’s work grapples with issues of translation and transmission. While Harkins’s work (Cherokee/Muscogee) sought to preserve Indigenous language through contemporary use and intertribal song transmission, Collod’s practice interrogates the limits and possibilities presented by methods of capture and preservation in dance.

Indeed, questions of notation and preservation in dance have been a throughline for Collod throughout her career. She cites her introduction to Labanotation—a system for notating and analyzing movement—in the early nineties as what inspired her to begin recreating 20th-century choreographic works from scores. In Labanotation, developed in the 1920s by Rudolf Laban, a series of symbols, not unlike a score for a piece of music, correspond to a particular body part and represent a single movement’s direction, level, and duration. Laban scores can become increasingly specific to allow spatial nuance, dynamic variation, and the temporal relationship between movements to be stated. As a tool, however, Labanotation has its setbacks. It is difficult to master, time consuming to generate, and fails to account for the cultural or historic context of a dance. To its credit, it is the only system of notation that can be used to copyright a piece of choreography.

Using this system, Collod, in collaboration with Quatuor Albrecht Knust, a collective of performers she cofounded, has recreated a number of pieces, including Vaslav Nijinsky’s legendary ballet from 1912, Afternoon of a Faun. She has also worked extensively on the work of Anna Halprin, including in 2009 when Collod brought her Bessie Award–winning restaging of Halprin’s parades & changes, replays to the MCA. Anna Halprin, whose early dance training included studying the techniques of Ruth St. Denis, was a pioneer of postmodern dance in the 1950s. She used another scoring technique to document her dance constructions. Reacting to the compositional and stylistic constraints of the preceding generation of dancemakers, Halprin validated the use of everyday movement and advocated for collective approaches to dance composition. Exploring the capabilities of her own body, Halprin created a systemic way of moving using kinesthetic awareness and written scores to cocreate her dances with other performers and audience members. Along with her rigorous, politically charged examinations of choreographic structures, improvisation, collaboration, and technique, Halprin’s scores, like that of Parades and Changes, were organized around a series of discrete, movable sections called “cellblocks” around which the choreography was based. Each cellblock was a score in which a series of activities was performed, but each task was altered or transformed by conditions such as speed or location. Not only is it impossible to recreate Halprin’s dances precisely, but variability was intentionally built into the score.

Regardless of the efficacy of these two methods of preserving dance, or the intentions of the dancemaker, what’s unavoidable is that dance will always be ever-evolving in relation to the conditions in which it exists. Whether in a new venue or performed by a new performer, each night a new audience enters the space of the dance, thereby creating an entirely new experience. This is both the magic and tragedy of such an ephemeral form. Reflecting on the disappearing dance archive that lives within her own body, another postmodern dance icon, Deborah Hay, has written that her “body, the archive, will not be archived.”[1] While it’s true that no one, perhaps not even Hay herself, could ever recreate a dance exactly—given dance’s moment-by-moment transformation in relation to history—the ephemerality of dance is what enables artists like Collod and her international cast, whose own narratives have been marginalized from the Western canon, to introduce themselves to the work and remake it in their own image.

Anne Collod, Moving alter-natives, 2019. Photo: Jacques Hoepffner.

Collod’s Moving alter-natives opens new possibilities for today’s audiences to experience the works of Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis. These particular restagings are complicated beyond questions of archive and transmission by contemporary considerations of cultural appropriation and how dance history is constructed. Contending with subject matter mired in the ignorance of the past is always challenging for artists seeking to refocus our thinking in more expansive, inclusive ways. Nevertheless, it is through these critical interpretations that we come to a greater awareness and clarity in the present, a greater imagination for the future, and perhaps even renewed fondness for familiar works.

Explore Further

Learn more about the complexities of Indian dance history:

- Read Lakshmi Ramgopal’s blog on “Dancing the Classical”

- Listen to the Pillow Voices podcast, “The Complexities of Indian Dance at The Pillow.”

Notes

[1] Deborah Hay, “My Body, The Archive,” in The Sentient Archive: Bodies, Performance, and Memory, eds. Bill Bissell and Linda Carusa Haviland (Wesleyan University Press, 2018), 199.